True Tales: Judging a Book by Its Cover

By George T. ComeauThis column has always endeavored to discover stories that have their roots in Canton and are historically connecting us through time. In this author’s youth, there were always great stories told within the four walls of the Canton Historical Society. Some of the stories were so fantastical that one would often question the veracity of the tale. Often times the stories were handed down with a wink or a sideways glance. In one famous piece of advice, Edward Bolster, then town historian, advised, “If you do not know the answer to a question, make it up!”

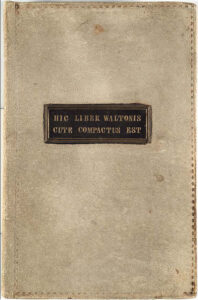

The deathbed confession of George Walton was bound in his own skin at his request. (Collection of the Boston Athenaeum)

Needless to say, credibility in this column stands up to scrutiny and the stories I heard in my youth are now questioned with a new lens and new tools for confirmation of facts. One such story that has long been told is that of The Highwayman. I can recall being told the tale when I was quite young. It is relayed here to share how folklore and fact blend to make a fabulous yarn rooted in nuggets of truth and embellished over time.

The story was printed in 1883 and again in 1922 in the Canton Journal under the headline “The Highwayman of Ponkapoag.” The unknown writer relays the tale of George Walton. The story begins with a tantalizing and macabre fact: “Some years ago a man named Walton was sentenced to the Charlestown State Prison for life. He died in that institution and his body was given to the surgeons for anatomical study. One of them skinned his back and when the life of Walton was published, the physician had the skin converted into leather and bound his copy with it.”

Anthropodermic bibliopegy is the practice of binding books in human skin, and confirmed examples, while rare, do exist throughout the world. In this case, deep inside the holdings at the Boston Athenaeum is a custom-made archival box and inside that box is the memoir of the career criminal James Allen, alias George Walton. The light gray cover bears the Latin phrase “Hic Liber Waltonis Cute Compactus Est” — “This book was bound in Walton’s skin.” Born in Lancaster, Massachusetts in 1809 to a struggling family, Walton fell into a life of crime at the age of 15, after a chance meeting with a master thief. The connection to Canton is strong and was the locus for one of Walton’s earliest attempts at highway robbery.

In the vault at the Canton Historical Society is the transcript of the connection. There is a small notation next to the index that reads “not much true in the story.” But there is in fact much truth in the story as it matches several details and seems wholly credible. If it is to be believed, a robbery in Canton aligns nicely with the life of a career criminal and thief of renown that was quite famous in the early 19th century.

On several typewritten pages is the account of an unknown man who supposedly was attacked by Walton on a twilight evening in 1824. “Drive over the spot as mellow twilight casts her velvet shadows, and though you may enjoy the wild seclusion you will find yourself inclined to give your horse the reign, and mayhap, a little of the whip or spur besides.” In short, a rather dark and scary part of the journey from Boston through the woodland road leading to Canton.

The account of this local merchant reads, “I had just passed a point about midway between Ponkapoag and the farther extremity of the wood, where a road, branching from the main road, leads still deeper into the forest, and was just rising to the summit of the hill that forms the road at this point, when I was overtaken by a single horseman. As we reached the level together, he turned his horse and dismounted, seized the bridle of mine, directing me in a calm voice to stop. I drew up my horse, satisfied that I was about to realize one of the adventures that had so often suggested themselves as I passed the lonely wood. His horse, as if aware of his master’s purpose, stood like a statue when he had dismounted from him.”

What transpires next is the brazen attempt at robbery of this merchant on his travel through Canton. Our local hero writes, “I sprang with the whole force of my body upon the man. He was utterly unprepared for this, and had evidently taken me for far easier prey … my first effort was to pinion his arms, nor was I a moment too quick in accomplishing my purpose, for as I bore down, that hand already contained a pistol, which at the same moment was discharged into the ground.” The writer then goes on to describe how he disarmed Walton of a pair of pistols and a Spanish knife and bound his wrists securely. “Having done this, I took out my pocketbook, and showed the robber that if he had succeeded in his murderous intent, he would have reaped a harvest of 10 dollars, and for this paltry sum he would’ve committed murder. I determined to leave the man to his own reflections, discovering as I thought, symptoms of true regret in his speech.” Unpinning his hands, and relieving the young boy of his weapons, the merchant rode off.

The next day the merchant left for New York City and subsequently on a sailing packet for Europe. After five years overseas, the merchant returned to America and had forgotten about the attempted robbery. In 1834, 10 years after the incident in Canton, Walton attempted another highway robbery upon a wealthy man named John Fenno Jr., who was returning home along the Salem Turnpike close to Chelsea. “I recognized him by his dress,” Walton recalled in his memoir. “I immediately walked from my position to the wagon, seizing the reins of the bridle, presented my pistol and demanded his money or his life…”

The Highwayman’s connection to Canton was first reported in 1883 and again in 1922 and the transcription is in the collection of the Canton Historical Society.

In the course of the robbery, Walton’s gun discharged and glanced off a metal buckle, thus saving Fenno’s life. So outrageous was the murder attempt that within days Walton was caught. After a life of crime, several daring prison breaks, and thousands of dollars stolen over the course of his career, it all came to a stunning halt.

On February 21, 1834, Walton was sentenced to “confinement and hard labor in the State Prison for 20 years.” While awaiting trial for a second robbery, Walton attempted suicide. Facing a life of confinement, he said that he then “formed a plan for terminating my existence.” The plan failed. By September, Walton had again escaped from prison. Seven months later he was apprehended near Boston. In early November 1836, Walton stood trial in Dedham. In February 1837, Walton was admitted as a patient in the prison hospital. Tuberculosis took hold and on July 17, 1837, he died in custody.

Prior to Walton’s death, the Canton businessman who had been robbed more than a decade earlier experienced a “strong desire to see the criminal” and paid him a visit in his cell. “In Walton, the highwayman, I discovered the robber whom I had by a singular coup de main overcome in the woods at Ponkapoag,” he recalled. “The recognition was mutual and it was with a strange wildness that he exclaimed, ‘Have you, too, come to witness against me?’” The two men fell into a long conversation and their encounter ended late that afternoon.

Several years after their encounter in Walton’s cell, the Canton merchant attended a medical lecture which featured an exhibit of not only the skull of Walton but also a book bound in his skin. Before he died, Walton told his stories to the prison’s warden, and asked him to write them down. He also made a more unusual request: “Allen asked that enough of his skin be tanned to provide bindings for two copies of this memoir.” One copy of the book was to go to his doctor, and the other was to go to John Fenno, Jr., who he considered to be “the only man who had ever stood up to him.” The binding has been scientifically confirmed to be human skin, according to the Anthropodermic Book Project — a group that seeks to confirm or deny cases of books allegedly bound in the material.

In Canton, we have perhaps the second person to have stood up to Walton. “Little did I think when I unpinned the arms of the highwaymen, who could’ve taken my life, in the lonely woods of Canton and Stoughton, that I should live to see his life printed and bound in his own skin” … If the story is to be believed.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=84001