True Tales from Canton’s Past: I am Guilty

By George T. ComeauThe following is the second in a two-part story about Jack Battus, one of Canton’s most notorious murderers.

As a distant church bell tolled midnight, Jack Battus was counting the hours of his last day on earth. Salome Talbot was only 14 years old when Battus took her life in the woods near her Ponkapoag home. The details remain vivid, and in his words the moment was vicious, primal, and most evil. In his final days on earth, with the assistance of his jailer and a local newspaperman, Battus wrote letters to all the people he knew in this earthly realm.

Dedham Jail, August 3, 1804: “To Mr. David Talbot and his Wife … My dear, but much injured Friends, (if by that title I am permitted to call you) having the sense of the unhappiness and extreme misery I have brought you into, I thought it my duty to write you from this my gloomy cell; and on bended knees, humbly, heartily and feverently to ask your forgiveness for what I have done.”

What Battus had done was “commit the most horrid crimes ever done in this Christian country.” And at the time he was writing letters to the mother and father of his victim he was in an iron cell, which he described as a “dismal abode, studded and inlaid with many bars of iron, with treble locks, as if I were a monster (as indeed I am) too disgusting and dangerous to intermix with civilized society.” The crime was only the second murder in Norfolk County, the previous one being only two years prior. Yet this murder was more heinous — in both depravity and the act itself.

After dragging Salome Talbot into the thick bushes near the road to her house, Battus threw her on her back and “in a manner unpracticed by the brutal species, deaf to her struggles, her cries and entreaties — disrobed her of that virgin purity, which is the flower and pride of her sex.” It was a vicious act, and when it was over, the fiend inside Battus grew even larger. Not content with the sexual assault, Battus found “the path lined with objects that induced him to engage deeper and deeper in the black work.” To cover up his rape, he would murder the child, an inducement of which he undertook in order to conceal the fact that his victim was “like a lamb in the voracious jaws of a lion.”

Battus could have simply left her there and fled. Rape, although a serious crime, was never met with the death penalty. In fact, there had only been one previous legal death sentence in the county — and that was for murder. Battus sensed the worse and picked up a rough stone, weighing about 15 pounds, and struck Salome on the head. Leaving her for dead, he felt as if the “embowering trees” were weeping. In fact, it was Salome weeping, and rising slowly as Battus walked away. Gathering her footing, the girl staggered down the path, and Battus once again pursued and again used a stone to bring repeated blows again to her head. Salome groaned and “cried most piteously,” causing Battus to drag the child through a small bog and dispose of her body in the pond. The will to live, however, was strong, and in a short period of time Salome drew herself out of the water and onto the bank of mud and muck.

In his confession Battus described the ending: “I again pushed her in; and taking up a stake or piece of rail, struck her several blows on the back of the head; when she sunk under the water, I left her thus, and saw her no more!” The crimes had been most evil, and Battus’ conscience immediately kicked in. “Every eye seemed turned upon me, and every moving lip pronounced me the object, who ought to be detected and punished.”

At the Talbot house, the non-appearance of Salome did not raise an immediate alarm. It had been her practice to stay overnight at the farms in the neighborhood, yet by Friday night Mehitable Talbot began to be concerned. On Saturday morning, two days after Salome had left to pick fruit, her mother began to walk to the Davenport farm. On the path was the brook and pond where no more than 24 hours ago Salome gasped her last breath.

The contrast was striking. From the black mud, the blue dress with matching petticoat and lifeless form of her daughter floated. A piercing scream cut through the morning mist as the mother fell to the ground. Within minutes neighbors, families, and friends all gathered at the site. Numbness fell over David Talbot as he tenderly carried his daughter to their house. And the next day, again, the child was carried to the meetinghouse at Canton Corner where a funeral was said and her body confined to the silent grave. There had never been such a grievous event in the history of the town, and after the burial, the eyes of the townsmen fell upon finding the perpetrator.

The meetinghouse at Canton Corner from which Salome Talbot was mourned (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

On the same night as the funeral, Battus fled. Immediately, he was a wanted man. Sixteen men were dispatched, four in each direction of the compass. The intention of this fiend was to escape towards Providence, then onto New York, where the murderer would dissolve into the city. That first night, Battus slept in the woods in Sharon. On July 4, after spending a whole day in a mosquito-infested swamp, he heard salvos of celebration coming from Taunton Green. Finding refreshments, he feared capture and again melted into the woods. Finally, on July 6, at a place called Balcom’s Tavern in Attleboro, men from Canton captured Battus.

Upon his return to Canton, he was examined by Esquire Crane, and without hesitation confessed his guilt. Battus was indicted on three counts. The first count charged the killing to have been with a stone with which he beat and broke her skull; the second stated that the killing was by drowning; and the third charged the killing to have been by beating and breaking her skull with a stone and throwing her body into the water and suffocating and drowning. There was another indictment against the prisoner for committing a rape on the body of the said Salome on the same day on which the murder was charged to have been committed.

Battus was placed in a small, dank cell inside the Dedham Courthouse. Within days he began writing letters to his “aged and affectionate Mistress,” that being Mary Blackman, the wife of Adam Blackman. “It is a long time I must lay in this iron room, before I can have my trial … Pray, do not fail to come and see me as often as you can, while my abode is in this melancholy. Dismal place, before I go, whence I shall never return; even to a land of darkness, through the dark veil of death! — Are not my days few?” In the life of this 19-year-old servant, indeed his days were numbered.

Over the course of his confinement in jail, Battus was visited by quite a number of “respectable gentlemen from Boston, Roxbury, and other neighboring towns.” With the assistance of Samuel Doggett, his jailer, a series of letters were written, all seemingly used as prophetic propaganda to illustrate the moral lesson before the reader. Writing to his victim’s parents, Battus exclaims, “I hope it be a loud warning to all young folks, both black and white, to resist the temptation of the Destroyer, who walketh about as a roaring lion, seeking whom he may devour.” A parade of clergy made their way to his cell to comfort and place Battus in prayer. Canton’s Reverend Zachariah Howard made several visits to the condemned man and seemed to comfort Battus in his last days.

The trial was set for October, and the Massachusetts Supreme Court was sitting in Dedham. Battus was the second case in that session, the first being a lawsuit brought by Paul Revere against his neighbors over water rights. James Sullivan, the attorney general of Massachusetts — and a friend of John Hancock and John Adams — handled the prosecution.

Battus stood tall. “Guilty,” he exclaimed. This was the first American guilty plea, and the court was perplexed. Chief Justice Francis Dana informed him of the consequence of his plea, and that he was under no legal or moral obligation to plead guilty, but that he had a right to deny the several charges and force the government to prove them. Battus would not retract his pleas, whereupon the court told him that they would allow him a reasonable time to reconsider. They directed the clerk not to record his pleas. The next day, Battus returned and again pleaded guilty, leading Dana to examine, under oath, the sheriff, the jailer, and Justice Crane as to the sanity of the prisoner and whether or not there had been tampering with him, either by promises, persuasions, or hopes of pardon, if he would plead guilty.

After a very full inquiry, nothing of that kind appearing, the prisoner was again remanded, and the clerk directed to record the plea on both indictments. Dana looked down upon the prisoner and sternly said, “Nothing now remains, but that I — however painful, pronounce Sentence of Death upon you. We are constrained, by your crimes, to deprive you of life … may God Almighty have mercy on your soul.” In a letter that same day, Battus wrote, “My fate is pronounced! — My earthly doom is fixed! Great God! It is thou who sealest my eternal destiny.”

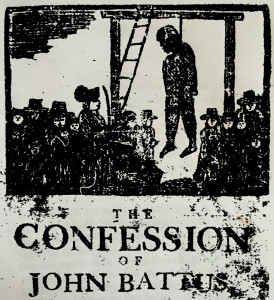

The wind blew violently across Dedham Common as Battus ascended the steps to the scaffold of the gallows. Four months and 11 days had elapsed since the rape and murder. And today was Battus’ last day on earth. He smelled the freshly sawn wood, saw the faces of those who came to watch him dispatched. In a final letter he wrote, “My life is like a candle burning in its socket. Am I prepared to die!” At the top step, Battus stumbled, and Reverend Joseph Grafton took him by the arm and gave him comfort. Battus shook the hands of the hangman — a fellow prisoner pressed into service. Shaking hands, Battus then drank a glass of wine to the executioner’s health. A hood of rough burlap was placed over his head. In his mind, Battus recited David’s Penitential Psalm, “Our life is ever on the wing, and death is ever nigh; the moment when our lives begin, we all begin to die.” John Battus became the second person executed in Norfolk County — and the first person in America to plead guilty for his crimes.

After Battus was executed, his body was cut from the rope and he was temporarily buried under the gallows. Within days, a broadside was published and soon thereafter a booklet of Battus’ letters and confession was printed. The body of Battus was dug up soon after he was hung and reportedly sold to Doctor Nathaniel Miller, a surgeon from Franklin. In 1805 the town of Canton paid $46.50, divided among the men who pursued the criminal. Mehitable Talbot lived out her life in Canton and died in 1830. Lost deep in the woods near Ponkapoag Pond are the remnants of her house.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=29480