True Tales from Canton’s Past: Razing History

By George T. ComeauThere is a wonderful little booklet published in the fall of 1909 that was printed by the Edison Electric Illuminating Company. The purpose of the pamphlet was to illustrate the advantages of developing commerce in the cities and towns adjacent to Boston. Largely, however, it was an economic publicity campaign to encourage the use of electricity and build the infant industry. If shared today, little of what is described still exists.

In 1909, Canton was a well-established town due in large part to its proximity to Boston and being situated on the main railroad line between Boston and New York. The description of the place is idyllic as viewed from the summit of Blue Hill: “Almost directly below are cultivated fields … elsewhere within the view are fields or meadows, smooth roads, occasional clusters of homes, the roofs of more detached structures, the stacks of industries and the spires of churches.”

Painting a picture of Canton more than 100 years ago is not all that difficult. We have a fabulous photographic record that is preserved at both the Canton Historical Society and the Canton Public Library, not to mention a few dozen private collections. What strikes a viewer of the photos are the changes that have occurred across what was once farmland and pastures. Most notably, take note of the changes to our neighborhoods and the need for larger homes to accommodate smaller families.

When Canton was incorporated in 1797, less than a thousand inhabitants occupied the 19 square miles we call home. Today, we have over 20 times that number of citizens. Securing services, land, and schools to support a modern American town has been a wonderful journey of deciding what is old and worth keeping, and what should be torn down to make way for new and modern ways of life.

At a recent meeting of the Zoning Board of Appeals the clash between old and new was presented in stark contrast. A pair of local developers sought permission to build a new two-family house by razing an existing two-family house. The house in question was built in the early 19th century and over the years was enlarged to become a stunning example of Queen Anne style architecture mixed against the backdrop of a superb Federal style home. The neighbors objected to the house being destroyed — not on the principle of historic preservation, but rather the principle of the creation of a new two-family structure in what has become a single-family neighborhood.

Historic preservationists look at two standards for deciding whether something is worth preserving. The first standard is the architectural importance; in other words, does the structure possess fine details that are exemplars of the architectural style? And the second standard is that of historical associations: Is there an example of people or events that are connected to the structure that help tell our story as a town? In both cases, the Spaulding house at 447 Chapman Street is historic architecturally and by association.

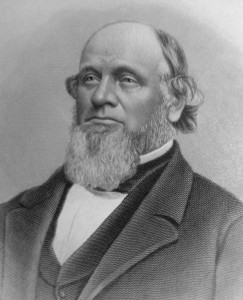

As you drive down the street, just to the south of the Chapman Street Bridge behind the untended hedgerow sits a grand house — built after 1841 for Corodon Spaulding, a prominent citizen of Canton. The property that makes up the Culloden Drive neighborhood was largely the 20 acres that was listed as Spaulding’s in the 1856 tax record.

Spaulding was born on January 1, 1812, in East Washington, New Hampshire. Growing up with a limited education, Spaulding left home at a young age to earn his way in the world. In 1830, at age 18, he took up work as a stonecutter and worked on Deer Island’s sea wall in Boston Harbor. The following October, he traveled to Newcastle, Delaware, and worked on the Frenchtown and Newcastle Railroad. In December of the same year, he worked on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. When the road was completed to Ellicott’s Mills, in 1831, he superintended a granite quarry that provided stone for the track on Baltimore’s Pratt Street. The following December, he went to Pennsylvania and worked on the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad. The next December, he left for his father’s home in Bradford, New Hampshire, where he stayed until the following March, when he began work at Boston’s Union Wharf.

In February 1834, Spaulding worked on the Boston and Providence Railroad as a tracklayer along the route. It is likely that Spaulding was integrally part of the construction of the Canton Viaduct and certainly would have lived here as part of the two-year construction project. In August 1835, Spaulding was promoted to road-master. During the course of his employment with the Boston and Providence Railroad, Spaulding invented a machine for curving and straightening railroad bars; this proved so useful that books hailed it as “so extensively used on all roads at the present time.” Spaulding also invented a derrick used by “all stone-masons” of his time. On April 20, 1836, he married Abigail Tolman of Sharon, with whom he had three children. In 1839, the couple moved to Canton; in 1841, they bought a small farm upon which the present house was built.

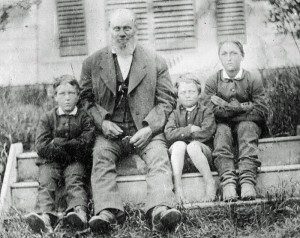

An old town history of Washington, New Hampshire, wrote of Spaulding, “Fortune smiled on his endeavors, and an ample fortune was the result. For many years he has resided on his farm in Canton, Mass., enjoying in peace and plenty, a serene old age.” Spaulding died in 1888, and his daughter Sarah married the local jeweler and clockmaker William K. Hawes. The Hawes family remodeled the house to include two-story turreted bay that exists nowhere else in Canton. As a result of this second renovation there are wonderful period details of impeccable quality within the house.

In November 2009, the last remaining section of Spaulding land was sold for $529,000 to a pair of local builders. In turn, the land was divided and two new houses were built and sold. One of the new houses at 190 Culloden Drive sold for $736,500 and the other at 180 Culloden for $570,000. Do the math — things are doing very well for single-family homes on Culloden Drive. It is easy to see why the developers want to tear down the Spaulding House — it means two more homes.

What will become of the Spaulding House on Chapman Street? It is hard to say, largely because the developers hope to maximize profits and the neighbors hope to minimize development. At the core of the matter is how to balance the need to make money with a moral obligation to the citizens of Canton. The fact is that there is sometimes a lack of vision at play in the decision to destroy a historical house in the heart of our community. The stewardship of a historic house is largely lost without vision and a keen support for our history.

Inside the Spaulding house are amazing details waiting to be restored. Upon the stone foundation sits a dusty old jewel. Framed with mortise and tenon joists typical of the early 19th century, the house is filled with period details. The front hall features a potbellied newel post of Italianate style, while a matching Italianate cast iron fireplace remains in the rear kitchen, likely matching the 1850s design.

At the front of the house is the original dwelling, complete with a formal center entrance framed by molded sidelights with stained glass inserts around the entry door. The façade is highlighted by a dentil cornice and shuttered windows. Federal revival fireplaces in the front parlor and real ell are all original to the house. If this house were restored, with an eye towards a modern buyer, it becomes a winning proposition for both the developers and the neighborhood.

Keep in mind that this property has already yielded two homes built by the same developers when they removed the historic dairy barn from the land. This barn fortunately was saved and moved to another town and rebuilt. High atop the barn in Canton was an ancient and historic running horse weathervane — whereabouts unknown.

And so the choices we make to destroy or salvage our history usually boils down to money. The moral question of preservation is rarely considered. In the early 1960s RCA Records demolished its Camden, New Jersey, warehouse by first dynamiting the building and its contents, then bulldozing the rubble into the Delaware River. “Through this single action, the record company notched a rare triple crown of destruction: It blew away a historic structure, polluted a famous waterway, and blasted four floors of cultural heritage — vinyl and metal master disc recordings — into oblivion.” The same thing is likely to happen here in Canton, with bulldozers ready to descend on Spaulding’s Chapman Street home. While not as historic as the RCA Record vault, nonetheless this house is part of our national heritage and tells a unique story.

When the town loses the Spaulding house no one leaves unsullied as a result — the developers, the Zoning Board, and the attorneys arguing for the demolition. Everyone is in a position to save this structure; the question that remains is who will step forward and save the Spaulding house.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=22044