True Tales from Canton’s Past: Martyr to Science

By George T. ComeauOn a bright Friday afternoon on May 19, 1922, Atherton Dunbar returned to his laboratory in the basement of the Jefferson Physical Laboratory at Harvard University. It was just after lunch, and the budding scientist was working on a very important project in the cryogenic engineering lab that was both of military and industrial importance.

Harvard’s Jefferson Laboratory was named in tribute to Thomas Jefferson Coolidge, the great-grandson of the third president of the United States and an avid patron of science. Opened in 1884, the building would become a “breeding ground of some of the world’s foremost physics discoveries,” including the famous Pound-Rebka experiment, which confirmed one of the predictions of general relativity (that gravity can change light’s frequency).

Atherton Dunbar at age 2 with his mother, Anna Marsh (Hewett) Dunbar, in 1897 (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

The laboratory is the oldest university building in America built specifically for the pursuit of physics. And of the 43 Nobel prizes received by Harvard University faculty, one quarter are held by physics professors. This was a building in which the pinnacles of many illustrious careers were achieved.

By age 26, Atherton Dunbar had already accomplished more than most men twice his age and was well on his way to a career in physical science that would harness physics and create opportunity through a physics breakthrough. Born in Canton in 1895, he came from prominent local stock, with both parents coming from a long and distinguished founding family.

Dunbar graduated from the Eliot Grammar School in 1909, and after attending Canton High School for a year, the family moved to Brookline and the young physicist attended Brookline High School, entering Harvard by examination a full year before his educational advisors believed it possible. While in college, he concentrated on chemistry, while also taking several courses in physics. World War I had started in 1914, and the United States entered the war on April 6, 1917. On June 19 of that year, Dunbar left Cambridge and joined a submarine chaser crew in Marblehead, receiving his degree from Harvard in absentia.

Attaining the rank of junior lieutenant, Dunbar served for two years before returning to Harvard in January 2019 to begin his graduate studies in chemistry. That same year, he married Miss Luena Nelson of Cambridge and they began a life together. With an extended family in Canton, Dunbar made frequent visits to his hometown.

His contemporaries and academics described the researcher in glowing terms. “I have seldom known a man better fitted for research work,” one observer noted. “He had great manipulative skill, that is, the ability to do anything with his hands supremely well; he also had a fine, keen, clear brain; and, best of all, he had initiative, he kept his job going and growing for himself, and most of the help that the rest of us gave him consisted of encouragement and appreciation. Any one of these qualities raises its possessor above the average; the combination of all three is extremely rare. His temperament also was ideal for his work. Happy, eager, indefatigable, unafraid, he brought to his work an enthusiasm that surmounted all obstacles, and inspired all who knew him.”

The work that Dunbar did was very serious and critical. This included an assignment given to him by the U.S. Bureau of Mines as part of their effort to put the production of helium for balloons on a sound engineering basis. Dunbar was concerned with the accurate determination of the vapor pressures and relative gaseous and liquid compositions of liquid mixtures of nitrogen and methane. The lab at Harvard had the most state-of-the-art equipment, and Dunbar, who lived less than 10 minutes away, spent a lot of his time working on his research.

On the afternoon of May 19, 1922, Dunbar had been in the basement lab all day “experimenting on the mixing of a liquid oxygen and liquid nitrogen.” Shortly before 3 p.m., he had just about finished his work when he turned to a coworker named Barnet Dodge and said, “I’ve a pressure of 1,500 pounds to the square inch,” and pointed to a tank that was being pumped with oxygen from an outside balloon. Within moments of the conversation, Dodge said there was a “sudden deluge of brick, timber, glass, and plaster,” which swept him off his feet. Buried under a pile of debris, the dazed man looked around, staggered to his feet and dove through a nearby window. Around the scene, dozens of other researchers were running from the wrecked laboratory building, many of them “staggering and bleeding from their injuries.”

Dodge was injured badly, and his entire right side of his body was a “mass of contusions and abrasions.” Holding the hand of his young wife, he learned of the fate of his friend, Dunbar. The newspaper reporter wrote, “Dunbar, martyr to the onward striving of science, was killed instantly and his body dismembered.” So great was the explosion that it was heard more than a mile away. The entire basement was wrecked, and the ceiling above — which was the first floor of the building — was razed with such force that classrooms of students had their ankles and legs broken by the shock of the blast. One account of the explosion described the students above as being “tossed about like toy men in a child’s house of play.”

A student on the third floor of the building was thrown 10 feet from his standing position. A small fire broke out and was swiftly extinguished.

Nearly all the windows throughout the building and the adjacent law school were all blown out.

An investigation was launched soon after to determine the cause of this catastrophe. It seems that just a month before, Dunbar had been injured in a small explosion that required hospital treatment. Undaunted, he returned to work just days later. The work that was being done required the use of liquid oxygen, which would explode forcefully upon contact with combustible substances.

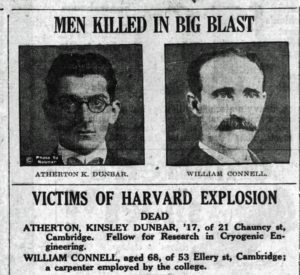

The search for the injured took several hours. And when all was reported, there were two deaths — Dunbar and a 68-year-old widowed carpenter by the name of William Connell. Eight students required hospitalization. The loss of the young man was felt profoundly by the entire family, town of Canton, and the university community.

A year later, a new laboratory for cryogenic research was established and the friends of Atherton Kingsley Dunbar gathered to pay tribute. During World War I the building had been used as an artillery shed and was later utilized for geophysics experiments. The new lab was housed in a one-story frame building and could compress gasses at pressures up to 3,000 pounds per square inch. The research in the extraction of helium was designed to be used for filling dirigibles.

The Dunbar Laboratory was demolished in 2003, but the legacy of its namesake still lives on more than 100 years after his tragic passing. Just weeks ago, in fact, descendants of the family donated a childhood photo of Dunbar to the Canton Historical Society — a remarkable find that will only further our understanding of one of Canton’s brightest young minds.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=118989