Canton’s True Tales: The 35th U.S. Colored Troop

By George T. ComeauThe following is the second in a two-part series. Part one appeared in the February 11 edition of the Citizen.

The book is thick and heavy with a leather cover, gilded pages and a brass clasp. From a distance it is imposing, and up close it instantly bears the weight of history. Embossed on the cover in gold leaf reads “Officers Association, 35th Reg’t U.S. Colored Troops.” There is no doubt that this is a book that embodies our national history and opens a long-lost door into a time and place of pain, suffering and eventual emancipation of 3.9 million slaves. The book is nearby on my desk as I write this story. History vibrates from the photographs inside. This is a glimpse into a military history that started with the Emancipation Proclamation.

On September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that as of January 1, 1863, all enslaved people in the states currently engaged in rebellion against the Union “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” But although it was presented chiefly as a military measure, the proclamation marked a crucial shift in Lincoln’s views on slavery. Emancipation would redefine the Civil War, turning it from a struggle to preserve the Union to one focused on ending slavery, and set a decisive course for how the nation would be reshaped after that historic conflict.

Upon hearing of the proclamation, many slaves quickly escaped to Union lines as the Army units moved south. As the Union armies advanced through the Confederacy, thousands of slaves were freed each day until nearly approximately 3.9 million were freed by July 1865. Massachusetts was the first state to form black regiments and send military men as leaders to train former slaves to fight for the cause of freedom. Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew called for men to lead experimental units who were “young men of military experience, of firm anti-slavery principles, ambitious, superior to a vulgar contempt for color, and have faith in the capacity of colored men for military service.” This call perhaps produced more active abolitionists for the 54th and her sister regiment the 55th than any other regiment in the North. But there is another regiment, the 35th, that may not have received the same notoriety as the 55th and 54th, but is no less valiant and critical to the victory of the Union Army.

The 35th United States Colored Infantry was composed of African American enlisted men commanded by white officers and was authorized by the Bureau of Colored Troops, which was created by the U.S. War Department on May 22, 1863. In Massachusetts, Governor Andrew felt responsible for taking the lead in organizing black units. Andrew stated in a letter to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, “The truth is that unless we do it, in Massachusetts, it cannot be expected elsewhere. While, if we do it, others will ultimately, and indeed soon, follow.”

In the same letter to Stanton, Andrew addressed the question of who would lead the brigade. It had to be a careful selection. The governor believed that an officer chosen to lead black soldiers should support the idea of arming blacks or, in the best case, have abolitionist sentiments. In addition to these moral attributes, Andrew sought a colonel who had seen action in the war and proved his abilities. By late April he settled upon Colonel Edward A. Wild of the 35th Massachusetts. And, in turn, Wild looked to others for support when choosing officers to lead the new unit.

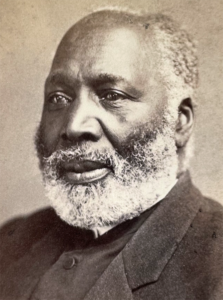

Rev. John N. Mars was the company chaplain and one of only two black officers in the 35th. (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

In the case of one individual, Leonard Lorenzo Billings of Canton, is revealed the political connections and the personal convictions that influenced Wild in his selection of officers. Billings had served as a corporal in the 29th Massachusetts Volunteers and had seen combat. He was recommended to Wild by Edward W. Kinsley, a close friend of Governor Andrew who, in a letter dated September 1863, included the governor’s warm greeting and summarized the Billings’ qualifications. “He is,” wrote Kinsley, “Anti-Slavery. Temperance ultra — and a good soldier.” Billings received a commission as a second lieutenant.

Billings would write, “Upon arrival at Norfolk, I reported to General Wild, whom I found to be a fine man and an able general, as well as surgeon. Leaving him, I went to Fortress Monroe and was sworn in by general B.F. Butler, mustering officer, as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Volunteers.” So began the second tour of duty of Billings, who had seen the war at an early age and whose convictions carried him back against the wave rising to free fellow human beings.

The tide of the war had turned in the favor of the Union, and once again, Billings recalled firsthand the view from the southern lines. The recollections are searing: “Going up broad river, we landed at Boyd’s Point, marching for three or four miles overland with four or five regiments in line of battle, intending to push the enemy and then charge. We pushed ahead all right and found the enemy. Firing a volley, we rushed at the rebels through the woods, field, and swamps, and away they went. Cannons opened up immediately, our force on the left had to fall back, and then we had to do the same. It was warm fighting for a time, our regiment losing 175 men killed, wounded, and missing, Colonel Beecher, Captain Whitney, Lieutenant Krebs, Lieutenant Stone and Lieutenant Ambler were either wounded or disappeared. The 54th and 55th Massachusetts regiment got it very severely. As for our regiment, after following back a distance and drawing the enemy out of the fort, we formed a line in an open field, along with a New York battery and a Captain Titus. While lying side-by-side with Captain Armstrong of our Company K, in front of the battery, a piece of wood and tin that held a canister together hit and scraped the captains head, after cutting his hat. After the battery had fired 55 charges, we were the first to rush the enemy, who broke and ran. It was now dark, and I was so wet with perspiration that I could wring the water out of my shirt.”

Billings described in detail his life fighting side by side with former slaves, now as equals. On February 20, 1864, the 35th Regiment had taken part in the Battle of Olustee. It was the largest battle of the Civil War fought in Florida and involved more than 10,000 soldiers, including three regiments of black troops. When the five-hour fight was over, Confederate forces claimed victory, and Union soldiers retreated to Jacksonville, where some remained until the war ended 14 months later. Billings recalled, “The regiment lost 280 men and 13 officers killed and wounded.”

The end of the war finds Billings at Mount Pleasant, overlooking the bay and harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. He wrote of the end of the war in a matter-of-fact tone: “On April 14 came to us the news of Lee’s surrender, and everyone went wild. On April 19, we hear of the death of Lincoln, and, as everyone is much excited from the events of the last few days, Company K is order to re-enter the city to occupy the upper guard house, Captain Armstrong and I, with 75 of the company, being instructed to police one half of the city from the Citadel to the neck. On May 3, General Johnson surrendered his army, formally ending the war. Three days later, on May 6, the rebels in front of us surrender and come into the city, where our job becomes very busy, since martial law is proclaimed and everyone must have a pass after 10 o’clock at night.”

Leonard Lorenzo Billings in a press photo taken at age 95 in Sharon (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

The legacy that Billings left behind is a window into the Civil War. The 61-page recollection is neatly typed and written near the end of the soldier’s life. The book that contains the photos of the 45 officers of the 35th is exceedingly rare. And in a large oaktag envelope are the two commissions that Billings received while in the 35th, along with citations from the commonwealth of Massachusetts. And perhaps rarest yet is the large broadside that lists the men who led and fought — black names along white names, forever enshrined in the company roster. At the end of his service, Billings was the provost marshal in South Carolina during the reconstruction period. In the days before Lincoln’s assassination, Billings stood among those who reviewed the troops, and Billings frequently referred to that as the most proud moment in his life.

Today, there are men and women in New Bern, North Carolina who have taken up the historical record of the 35th. For the last five years a resurgence of interest in the 35th Regiment has led to the creation of a reenactment unit, some members of which are direct descendants of the men who fought with Billings. New Bern was the seat of recruiting for the U.S. Colored Troops. It is a place that Billings would have known. The 35th represented some of the finest leaders along some of the finest fighters in the conflicts of the deep south and Florida.

Bernard George is a historian associated with today’s 35th Regiment. “The 35th did not have the media following that the Massachusetts 54th and 55th had. That said, they had a fine record.” George also noted that there were two black officers in the 35th: the company reverend and a very fine surgeon.

The book and all the material that Billings collected will be scanned and shared with the people of New Bern. Canton now has a new-found cousin and history inexorably tied to the emancipation of the men and women from the dark chapter of slavery. We have Billings to thank for this glimpse of the record. And Canton’s connection is a telling indicator of the strength and conviction of the men who hailed from here and died in faraway places under the banner of liberty.

Billings’ final days were a whirlwind. In his 97th year, Billings decided to re-trace his Civil War service and started a 2,000-mile motor trip south to visit the battlefields of his youth. Accompanied by his daughter, Billings died in Charleston, South Carolina, on October 22, 1939. The old soldier was brought back to his house in Sharon, Massachusetts. “Flags were at half-staff, and business halted while Sharon’s ‘grand old man’ was born to his soldier grave in the Canton Corner Cemetery. Pallbearers from the local veterans post bore the flag-draped casket to the line of march on Pleasant Street. School pupils, scouts and townsfolk stood by respectfully as the cortege passed. A volley was fired by the firing squad and Taps was sounded by the post buglers.” Canton’s son was laid to rest with his father and at long last, the soldier came home.

Special thanks to the members of the 35th U.S. Colored Troops Reenactment Group and historian Bernard George.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=73018