Canton’s True Tales: 1906 robbery in Ponkapoag

By George T. Comeau

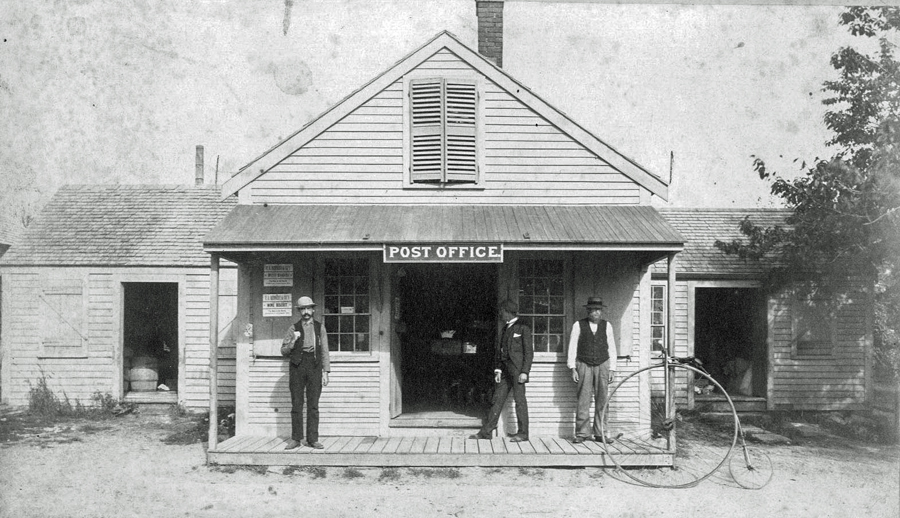

The Billings and Horton General Store and Post Office was located where the new condos are being built at Connor’s Wayside Furniture. (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

When big things happen in a small town the news can rush like wildfire. Tongues wag fast and the allure of a big crime story can be fodder for the newspapers for weeks. In the summer of 1906, big news literally exploded in Ponkapoag in what can only be described as a brazen robbery that shook the entire neighborhood.

At the time, Ponkapoag was a sleepy village on a turnpike that connected Boston with points south. The neighborhood was very close knit and everyone looked out for each other. The people that lived there were, for the most part, well off and well known. As is the case now — and was then — people were creatures of habit, waking and retiring to bed at set times. People took notice of strangers, and the alarm of a dog was as good as an ADT system today. That said, opportunities for criminal activity abounded.

The prime target of the crime was the post office safe. In 1906 there were three post offices in Canton. The one in the center of town was the main office and there was also one at Canton Junction. The third was a small office located in Ponkapoag inside the Billings and Horton General Store. Over the years burglars had failed to profit very much from postal safes. That never stopped them from trying. In one case at Billings and Horton, the “would-be robber was gathered in, in the act at the muzzle of a shotgun in the hands of the vigilant junior partner.” Imagine that scene in the small general store in the sleepy little hamlet.

The technique and professionalism of this robbery has to be admired. The skill and the escape, the intrigue and the red herrings. It was masterful, yet yielded little for the efforts. By the way it was described in the Canton Journal and the Boston Globe, it sounded as if Danny Ocean was pulling off Ocean’s Eleven.

The break-in took place around 2 a.m. on Sunday, August 12. Several folks nearby had heard noises, but a small gang of kids had been causing a ruckus earlier in the evening and the residents did not seem alarmed. The thieves gained access by jimmying a window on the northerly side of the building. Employing soap, the thieves sealed the seams around the safe door to create an airtight seal. Nitro-glycerin was pumped into a small gap and filled the interior of the safe. Several mailbags were then banked against the door to deaden the explosion. A charge was fired through the use of a fuse and all was in place. Taking cover, the thieves lit the fuse and waited.

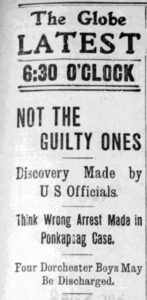

Newspapers from Baltimore to Boston reported on the brazen heist. Young men that had been accused were fully exonerated.

On the wall of the store was a master clock. As the moments ticked by, the perpetrators huddled nearby. BOOM!!! — the force of the blast was calculated perfectly. “It tore the door completely from the safe, shattering the hinges and breaking the wheel blocks.” As the impact of the explosion tore through the store, the fireproofing material inside the safe radiated and settled upon shelves and boxes nearby. Remarkably, the store windows stayed intact with the exception of one, through which a small piece of iron bulleted and shattered the pane.

The thieves took an empty mailsack and quickly filled it with the drawers and packages that they found inside the gaping box. The haul: $60 in postal cash and about the same amount in stamps. There was also $250 in non-negotiable checks. The largest value was a series of four $1,000 government-issued bonds. These could have some value if they could be sold to an unsuspecting buyer. The fact that they had been registered meant that they were valueless through conventional sale or trade. The thieves made off with their haul and dissolved into the night.

As the sun rose on Sunday morning, 16-year-old Quincy Lowry walked towards the back of the store to tend to the horses and “chanced to enter the store.” The office was a complete wreck, and the aftermath of the explosion readily evident. Lowry ran to the house of I. Chester Horton to report what he had encountered. Soon the alarm was spread to the surrounding towns. Postal offices were frequent and easy targets. A strikingly similar incident would take place in Randolph two weeks later. Same M.O. — timing at 2 a.m., nitroglycerin in a controlled amount, and a similar haul.

The postal police got to work and began investigating the brazen crime. Neighbors reported that several youth had been causing a disturbance and leads were sought. A few nights later, four young men from Dorchester were apprehended and held under suspicion. The thing was that these boys had indeed been “temporary rowdies.” The paper opined that the blast at the post office could not have been perpetrated by these boys. “The work was done by professionals, certainly by men who knew how to handle the explosive, and where to place it. Neither does it seem reasonable that parties contemplating such work would deliberately draw attention to themselves by creating a disturbance as did these boys for some hours on that night.” The prosecutor held that they indeed had been involved, owing to conflicting statements, as well as to their “idle life.”

Nevertheless, the boys were given bail and the investigation continued. Less than two weeks later, police in New York City arrested Harry Clark when he was caught trying to sell one of the $1,000 bonds. Police turned Clark over to the federal authorities in Boston under suspicion of being involved in the heist. By the end of the month, Clark was in Boston and the boys were exonerated. Once again the local paper put its two cents into the case. “Their arrest under suspicion may be a lesson to the lads who seem to be none too prudent in their behavior, and perhaps could be punished on a different and less serious charge, but lacking the strongest kind of evidence it was hardly a recommendation for the officer who directed the action and is not likely to inspire any greater faith in the ability of the postal authorities to secure the detection of thieves.”

It turns out that it was likely that Clark was the sole perpetrator. When he was arrested in New York, the gold bond certificate he was trafficking was signed by the owner, Leon A. Billings, a grocer from Ponkapoag. Incidentally, Billings was also the postmaster at Ponkapoag, and he had regularly stored his property in the safe. When Clark was arrested in New York, the papers described him colorfully as the “yeggman” that pulled off the plunder in the Canton robbery.

The excitement of that robbery was shrugged off by the local papers, but continued to be covered by the Boston and New York press. The boys, finally exonerated, were quite happy to have been cleared. Clark pled “not guilty.” It is assumed he was tried and convicted, but there doesn’t seem to be a historical record of the final outcome.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=72417