True Tales: Pt. 1 – Giving Thanks

By George T. ComeauBelow is the first in a two-part series about the Gelpke twins of Canton by True Tales author George T. Comeau.

Many families in Canton had reason to celebrate and give thanks on Thanksgiving Day on November 22, 1945. The war in the European Theatre had ended on May 8 as Americans and Allies erupted in celebration with the surrender of the German forces. And while there were still pockets of hostility and danger, for many families in Canton there was an enormous sigh of relief. Eight hundred and fifty-six men and women had gone to war, and 22 men had given the ultimate sacrifice for freedom in far-off lands.

Charles and Julia Gelpke sat down to a glorious Thanksgiving meal and gave thanks to the lord that the war had ended. Seemingly their three sons had survived the combat, where so many other families could only weep for those lost and dead. Corporal Arthur Thomas had died in Germany in May. Lieutenant Robert Brown was killed in Luzon in July. But the Gelpkes had just begun to relax. On September 28, the Boston Globe had run the photos of the three Gelpke boys in a story honoring all of the brave Cantonites. Soon, they would all return.

There were many family groups that had served, including famously the six Teague brothers and five Romanelli boys. When it came to families that sent four uniformed men, the number was staggering. The Globe wrote that the “Caddigans, Hinchcliffes, Mackiernans, Malcolmsons, Martis, Adamses, and Whittys” all sent four of their respective family members. Eleven families sent three — including the Gelpkes. There was even a brother-sister combination from the Bissell family.

The Gelpkes lived on Pleasant Street and Charles had built a considerable fortune as the right-hand man to John Meyers, the owner of the Springdale Finishing Company. Springdale had been part of the war effort, manufacturing tons of khaki uniform and tent cloth for use oversees during the conflict. Charles despised Franklin Delano Roosevelt, even while doing considerable business with the government and making his family fortune. During the Great Depression, Gelpke earned more than $15,000 a year — an enormous sum of money by any standards during a time of extreme hardship.

The fact was that Roosevelt had brought three of Charles Gelpke’s four sons into the war. This was unforgivable and he had a hatred for all that Roosevelt had stood for, mostly because his sons had been placed in harm’s way. 1945 was the first year that some normalcy returned to Thanksgiving. Many of the troops were coming home, Roosevelt had died earlier that year, and the town was raising money and jobs for the returning soldiers. A reception was being planned at the Legion with a December party already set on the calendar. Roy had been discharged from the Air Corps and perhaps Robert would be home from Germany by the New Year.

Charles Gelpke was a complicated man. He came to live in Canton in 1913 when he married Harriet Louise Estey, and they lived on land that had been in the Estey family for centuries and had two children. Within five years Harriet was dead at the hands of the great influenza epidemic that swept the country in 1918. Caring for the 4 year old and the 1 year old fell to the Estey grandparents until Charles remarried in 1922. A leader in the community, Gelpke served as a selectman in the 1930s.

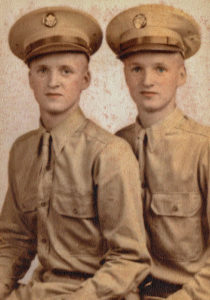

It was a close-knit family. There were seven children, including twin boys: Robert and Roy. The twins were born to Gelpke’s second wife, Julia, who by all accounts was an amazing woman. There would have been even more children, but another set of twins failed to survive a pregnancy. Charles was very strict and when it came to household chores he provided the finances, lit the stove every morning, and did all the grocery shopping. Julia raised the six children, including the two children from the previous marriage all as if they were her own. Christina Dunnell, a granddaughter, describes her grandmother as “simply amazing.” “There was a clothesline in the backyard that seemed to go on for hundreds of feet, and she did all that laundry by hand,” Dunnell recalled.

The twin Gelpke children were well known in Canton. They were inseparable from birth. They did everything together. Their best friends were the only other set of twins in Canton — the Holmes brothers. Taken together, Warren and Wesley Holmes and Robert and Roy Gelpke must have been a handful for the teachers who had to wrangle the inevitable hijinks and shenanigans that twins can be famous for. Together the four boys were part of a major Harvard study that focused on the development of twins that ran for more than 60 years. Warren died in 2014 and was still part of the study when he passed away.

So close were the Holmes and Gelpke families that Robert and Roy’s youngest sister, Mary, married Warren Holmes. There is still a bond between the families almost 70 years later. But as World War II began, all eyes in Canton were on the looming storm clouds overseas. When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Robert and his brother were 17 years old. Sitting in the parlor, knees akimbo and listening to the radio, they were wide-eyed to hear of the devastation in Honolulu. As 2,400 Americans died that day in December, the “date that will live in infamy” speech was broadcast throughout the nation. Charles Gelpke knew all too well what the future would hold. A father knows; a mother knows. War rips the soul from families, and Charles was instantly transported back to June 5, 1917 — the day he completed his draft registration card for the first World War.

In 1917, with a firm hand, Gelpke wrote that he was the father of two children with a wife, all residing on Pleasant Street in Canton. At the time, Gelpke was a stenographer at the Boston Molasses Company on Summer Street in South Boston. Immediately abutting the molasses factory was the Army Supply Base on Dry Dock Avenue. From his window, and through the sooty glass, Gelpke saw the tens of thousands of men who left Boston never to return from conflict. What father would not cringe at the call of duty, and so on his draft card he claimed an exemption from service specifying his three dependents.

In April 1942, Charles Gelpke drove to Dedham and filled out the second military draft registration card in his life, this time certifying that at age 53 he was ineligible to be drafted into the war effort. On this occasion, his age would keep him from service. Yet within weeks his two twin boys would graduate from Canton High School. At 17 years old, they were both underage for enlistment — although to the chagrin of their father, they both surely would have enlisted if given the chance.

Robert found employment at the Fore River Shipyard, and within a year, and of age, both Robert and Roy enlisted and began active duty on May 25, 1943. It was nearing the end of the war, and both young men were sent to Europe to fly bombers. Roy became a second lieutenant and Robert a flight officer.

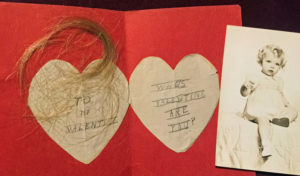

The valentine with a lock of hair given to the boys as a memento from home (Courtesy of Leslie Larusso)

Each day, both sons dutifully wrote letters home, letters meant to comfort and reassure a nervous stateside family. In one poignant letter a small cardboard handmade valentine was tucked inside for each of the boys. Inside the valentine was a lock of hair and a photo of the young men’s baby niece, Christine. To this day, Christine still chokes up to know that she has this memento from another time and place.

As Charles and Julia sat down to Thanksgiving, a prayer was said for Robert’s return. Given the end of hostilities, a safe return was seemingly assured. Meanwhile, 3,600 miles away, Robert Gelpke was sitting down to breakfast with his best friend. Second Lieutenant Harold Kotora had flown into the base at Hanau, Germany, and he was pleased to spend time with his close buddy. The two men had been roommates earlier in the war. They were comrades in arms; they laughed and joked. For some unexplained reason Kotora was nicknamed “Stan” when they flew together in a fighter group earlier in the war. “Bob” and “Stan” set off to chow down a Thanksgiving breakfast together. Less than two hours later, Canton would lose their 23rd son in the service of our nation.

Click here to continue on to part two of this story, “Day of Sorrow.”

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=45880