True Tales: Canton Milk Epidemic of 1913

By George T. ComeauOn March 3, 1913, the annual town meeting voted down an article that would have authorized the Board of Health to appoint an inspector of milk. Fifty-five days later, the Canton milk epidemic struck.

One hundred years ago the town of Canton looked very different than it does today. There was certainly a sense of community and safety, an idyllic place of merely 4,000 residents where everyone knew everyone else. The neighbor over the back fence was practically a family member, and people took care of each other.

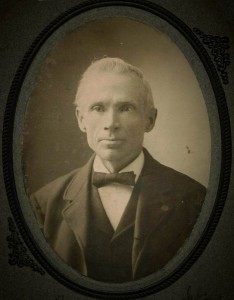

Dr. Dean S. Luce pictured in a Harvard class photo circa 1904 (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

Just about every day there would be a familiar face in the neighborhoods across town. The coal dealer made his rounds followed by the iceman, and of course the all-too-familiar milkman. But in April 1913, it was the milkman who brought sickness and death to hundreds of residents in this bustling little town.

Like wildfire, the symptoms began spreading across town at an alarming rate. People began reporting chills, fevers, dull and profound headaches along with nausea and vomiting. And while the individual symptoms varied, ultimately the sickness settled in the throat. Inflammation of the tonsils became so severe that swallowing and breathing was all but impossible.

The outbreak officially began on April 28 when the local Board of Health, headed by Dr. Dean S. Luce, called a meeting to discuss “a few cases” of septic sore throat. By late April the epidemic was in full swing and alarm began to spread across the community. People were suffocating and began to die at a noticeable rate. All eyes turned to the milk, as a similar outbreak in the milk supply had occurred a year earlier in Boston.

In Canton’s case, 26 dairies in the general vicinity supplied milk. Since raw milk was available locally, the supply was produced and delivered on the same day. Carefully, information was collected to try to discover similarities among the sick to determine the source of the illness. A striking fact: All the milk in the hundreds of households was coming from one source. It was not long before the cause of the milk-borne illness was traced to the dairy owned by a wealthy citizen, Charles Howe French Jr.

On Wednesday, April 30, Dr. Luce called the state Board of Health around 3 p.m. and tried to reach the state health inspector. Luce, a Harvard-trained physician, played a central role in combatting the epidemic. The next day Dr. W.W. Walcott arrived from Natick around noontime. The first stop was French’s Dairy on Washington Street. A graduate of Harvard College and of Harvard Law School, French was a prominent and well-respected citizen of the town. A member of the School Committee, he was the son of a prosperous industrialist who had built a fortune in the wool industry here in town. Having practiced law for six years in Boston, French ended his practice in 1908 and became a dairy farmer. When suspicion fell upon his dairy, the sense in town was that friends on the Board of Health stood by to protect him.

In reality, the Board of Health took the matter extremely seriously. A detailed day-by-day account was written a year after the epidemic. The report shows increased concern for the sick and dying as the epidemic raged. On the very first visit to French’s dairy, the inspectors and the entire board met with French, two hired men, the foreman, and anyone else connected with the milk supply. The inspection included examination of the 18 milking cows and a thorough examination of the premises.

The health team learned that French had fallen ill with tonsillitis the previous week and that members of his family were extremely ill. The foreman, R.E. Brooks, also reported being sick with the same malady “some time before.” Likely, Brooks started the epidemic by working while sick, thus infecting the initial milk supply as early as April 15. A fateful decision was made by the Board of Health to keep the dairy open and instruct French to stay away for the foreseeable future.

A letter arrived the next day from the state inspector suggesting that the “entire milk room be thoroughly scrubbed and disinfected” and that “all cans, bottles and utensils boiled.” Despite these measures, more deaths occurred in the following days. And, more alarmingly, children began to come down with a rash diagnosed as scarlet fever. Bottles being returned from infected homes were being refilled and infecting new households. The Board of Health stationed Thomas Dockray at the French Dairy to oversee the boiling and sterilization process.

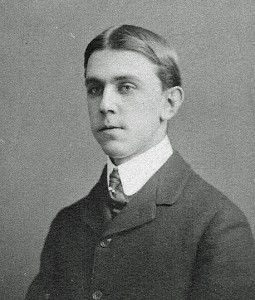

Former Police Chief Henry Galligan oversaw the sterilization and boiling procedures at the local dairy farms. (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

On Sherman Street, the Collins family closely watched their newborn infant son labor in his breathing. The illness that was sweeping Canton began to claim victims — those who were ill-equipped to fight off the infection. On Saturday, May 3, seven-month-old Charles Collins Jr. died of pneumonia. That same day, 73-year-old Mary Ellen Notman was slowly dying of septic tonsillitis.

After a weekend of hundreds of illnesses, the Board of Health took action and closed all schools and the public library. They also forbid any public funerals and advised parents not to allow children to play together, stating that the “benefit of closing the schools in a time of epidemic is lost if the children continue to play together, even though they are out of doors.” The School Committee balked at the idea of closing the schools, claiming that they could “protect the children better by watching them every day with the aid of the school nurse.” The state health inspector did not approve of the closing of the schools, “but such action was wholly in the hands of the local board” and the schools were kept closed.

In one case, a funeral procession was stopped and dispersed at High Street on the way to Knollwood to bury a young 23 year old. Churches were closed the following week and a state inspector observed that he was “absolutely surprised at the conditions of the sick and [he] had no idea that such conditions prevailed in Canton.”

At the same time, seemingly clandestine orders to fumigate all public buildings and dwellings of the sick were ordered. The cars of the Blue Hill Street Railway were disinfected twice a day. All the while, rumors burned through town. The most serious rumor involved the story that a “diseased cow was spirited away from one of the dairies in town.” This rumor had multiple sources and included nefarious versions that heightened the fear of the townspeople. Meanwhile, obvious questions began to arise as to how Mr. French’s milk was still being sold.

The Board of Health sought to calm nerves. In the weeks since the outbreak “nearly a half score of deaths” startled and panicked the community. The board reported that they “have thoroughly investigated all the dairies in town and have demanded certain improvements which have been installed.” Singling out Mr. French in particular, they reported that he “has installed machinery to pasteurize all milk which he handles and the public can rest assured there is no danger from the use of milk so treated.” The ex-chief of police, Henry Galligan, was ordered to visit all dairies and oversee the boiling and sterilization process.

By May 6, 200 people were seriously ill. The state cattle inspector soon came to inspect the herds and on two occasions took samples for testing. All the while the sickness continued, and the Boston papers reported sensational stories of people coming down with “Cantonitis.” The Boston Post described the work of the local and state authorities as “muddled and mismanaged” and exclaimed, “To the sick and to the families of those who have died this bungling will require a great deal of explanation.” By May 10 the milk supply from the French Dairy was formally cut off.

That same day, one of Canton’s venerable Civil War veterans succumbed. James J. Smith had enlisted at the age of 16 in Company A, 3rd Heavy Artillery and had survived the war and returned to Canton. The members of the local GAR Revere Post requested permission to hold a graveside service, and the Board of Health denied their request. In one of Canton’s most poignant moments, the members of the GAR Post formed in front of Memorial Hall and presented their colors as the hearse passed. The town was never able to mourn the loss of its war hero.

The state legislature took action and ordered that the Committee on Public Health be authorized to “summon witnesses for the purpose of [determining] whether the State Board of Health, or the Canton Board of Health, or both, were negligent in the case of the epidemic.”

By mid May the epidemic had begun to subside, owing mostly to the fact that pasteurization was required as part of providing the milk supply to Canton. In the end there were over 400 people gravely ill, mostly children and elderly, and nearly 20 deaths were reported.

In the years to come, infectious disease specialists studied the epidemic and it was determined that human streptococci growing in the milk caused this great tragedy. It would be almost 30 years until penicillin would come to be used to treat strep throat. French was sued for $5,000 by a fellow School Committee member who “decided to take the matter to court and have it decide where blame was.”

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=19936