True Tales from Canton’s Past: Something Fishy

By George T. ComeauOn a windy February night in 1804, Samuel Talbot sat at his desk in Stoughton and thought back over the year. Talbot had spent the last several months overseeing a controversy that had begun in 1727 that pitted wealthy mill owners against farmers and a way of life that was disappearing with the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. Talbot wrote with a steady hand, and each entry recalled the front-line disputes that pitted neighbors against neighbors along the Neponset River in Sharon, Stoughton and Canton. At the epicenter of the controversy was a small fish called the Alewife.

Massachusetts has the distinction of a tremendous history tied to the protection of natural resources. Indeed, the earliest fishing laws can be traced to 1623 when the Colony of New Plymouth enacted a law that declared hunting, fowling, and fishing shall be free. Within 14 years, the Massachusetts Bay Colony declared hunting and fishing to be free. The law in 1641 laid out the basic rights — the basic legal theory of which is still true today that “every inhabitant who is an house-holder shall have free fishing and fowling in any great ponds, bays, coves, and rivers so far as the sea ebbs and flows within the precinct of the town where they dwell.”

The natives as well as the Pilgrims used fish as both food and fertilizer. The codfish that hangs in the House of Representatives in the Massachusetts State House speaks to the strength of the fishing industry at the roots of our earliest economy and of the impact that fish have had on our development. Yet by 1727, the flames of controversy surrounding fish and the rights of men versus mills began to simmer. An article in the town warrant, in what is now Canton, asked the citizens to “see what action the town will take in regard to procuring a free passage for fish up the Neponset River.”

With the town meeting of 1727, the opening salvos were shot that set the stage for the next 100 years. The town of Stoughton had only been incorporated the year prior, and the first annual town meeting was contentious to say the least. The rights of the men who fished along the tributaries and the ponds feeding the Neponset River were being affected by the mills and the dams that were controlling the flow of water. The impact of the mills was immediate and would prove to be devastating to both the livelihood of the pioneers and the fish themselves. All along the streams in what is now Sharon, Stoughton and Canton the fish population plummeted.

The Alewife has many other names, but for the purpose of this story the best alternate names include the branch or river herring. In so describing the fish, we learn that it is a member of the herring family and is a migratory fish that is born in freshwater and then grows into adulthood in saltwater. There is an innate homing instinct that draws this small fish back year after year along the same rivers that feed the Massachusetts Bay. The spawning season begins in March and April and the babies leave the warmer ponds and streams for the ocean in late summer and early fall.

What made the Alewife so attractive to early settlers was the fact that they were so plentiful and easy to catch. A Canton historian wrote that, “The number of fish that journeyed to Canton was enormous. Before any obstruction existed to their passage, Ponkapoag and Pecunit Brooks were so filled with fish that a traveler, riding through one of these brooks, destroyed numbers of them with the tramping of his horse.” What’s more, these fish were worth a great deal of money to early citizens. The fish were eaten or smoked to preserve them for the winter. In many cases they were used as fertilizer for corn, and in 1758 they were sold as a commodity to “French Neuters” at two shillings per hundred. They were the lifeblood of the local settlers, and when the mills began to dam the streams leading inland, the fish were cut off.

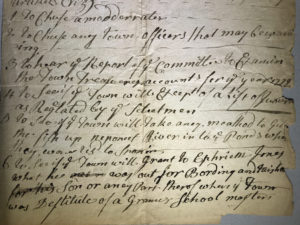

The town warrant for 1772 showing the town of Stoughton working to save the spawning grounds of the Alewives. (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

By 1766 the mill owners conceived of an offer that would further infuriate the citizenry. At the lowest dams along the river the mill keepers demanded that the towns “make and maintain a passageway six feet wide” that would remain open for one month during spawning season. The plan also called for the mill owners to receive £100 per year to the two owners of the mill. Needless to say, this was not a plan the towns would agree to and the controversy dragged on.

In 1783, the Honorable Elijah Dunbar, Canton’s own illustrious citizen, was appointed to present a petition to the Great and General Court asking that the mills remove the obstructions. Such great hope was placed on Dunbar that Sharon and Walpole joined the petition. The two most offending mill owners by the names of Daniel Vose and David (perhaps Daniel) Leeds decided that they would counter the petition by agreeing to open a sluiceway four feet wide “when the tide came in.” In doing so, the Court was relieved of answering the petition. And yet, the fishing stocks were not recovering. It was then that spies were sent from the upstream abutters to witness the obstructions and report back. On a dark night, Daniel Vose encountered “one of Canton’s myrmidons looking about his dam and threw him into the pond.”

Ten years later in 1793, both Vose and Leeds lost their rights to Stoughton and a year later to Sharon. Yet, despite that loss, mill owners were exerting great pressure on the water rights and the fish would lose out forever. The proverbial tide was turning and petitions to close the sluiceways were gaining traction and favor with the legislature. In 1796 mill owners petitioned that great damage and inconvenience was at hand if the mills had to close. The Neponset was being exploited for the power of the water to turn the wheels of progress.

The towns continued to fight the mills, and in 1803 the mill owners were required to keep their sluiceways open. And that led to Samuel Talbot’s appointment by the town of Stoughton — and joined by Sharon and Canton — to be the person who would “inspect the fish ways” leading to the several ponds in each town. Talbot’s work began in March with a meeting of the committee to which he served. On May 23 he found himself at the dam of Paul Revere and later that day at Jonathan Leonard’s. Talbot spent the rest of spring and early summer working to observe and protect the fishways. On the last week of June, Talbot spent three days reporting his findings to a committee on Beacon Hill. As a result of his work, the following year the legislature ordered that “fish must pass” and that alterations to the dams and sluiceways meant that water would flow uninterrupted for 30 days at the expense of the mill owners.

As the mills gained more wealth and work shifted from the field and plow to the wheel and forge, the controversy abated and the dams were fully restored. The expense of the fight for the fish was overshadowed by the growth of industry as a new economic engine. In 1809, 11 mill owners on the Neponset River petitioned the General Court for the right to end interrupting the flow of the river for fish to Massapoag and Ponkapoag ponds. The argument read that “after a fruitless experiment of such sluiceways being opened for more than twenty years last past, the only result has been great expense to the Parties, serious injuries to the manufactures, a diminution of the value of the Real Estate, and a constant excitement of the irritable feelings tending only to disturb the happiness of society.”

The fish population in the inland waters of Canton plummeted and what was left were the bass and trout and smaller species. The industry that changed the ecology of Canton roared onward. Samuel Talbot’s bill totaled $23. Today there are no Alewives in Canton.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=61000