True Tales from Canton’s Past: Alms for the Poor

By George T. ComeauEmeline Crane was born in Canton in 1829; by the time she was 28 she was likely insane and a guardian was appointed to oversee her affairs. At the age of 59, Crane died in Taunton after a life plagued with chronic mania. The Annual Town Report for that same year shows an appropriation for $32.65 paid to Billings Hewett to cover the expenses of her burial in Canton Corner Cemetery. A small gravestone marks the life and death of this troubled woman.

There are countless records of paupers, indigent, poor, lunatics, and the destitute chronicled in our town records. Several years ago, this author purloined a set of “pauper records” destined for a dumpster and now safely in the collection of the Canton Public Library. The records from the early part of the 20th century meticulously catalog the names and expenses associated with public support for the poor. This has been part of our town’s history since well before we were founded.

The earliest documents of the care of the poor are found in the Ancient Stoughton Records, where indigent are housed with families and the care and expenses are covered by the town. The catch was that if you were poor you had to leave Canton unless you were from Canton. And if you were from a neighboring town, a bill would be presented to that town for the care and welfare of one of their own. Special “swearing out” warrants would be presented by the selectmen if they found someone within the town borders who did not have sponsorship to be within the town.

It is a sad legacy to share. In the mid 1700s the selectmen took up the question of building a town almshouse. The question was presented as early as 1759, and again in 1766 and 1783 — all to no avail. Instead, in an archaic fashion, the poor and the insane were literally auctioned off annually to the lowest bidder who would “take the unfortunates to his home to provide lodging, nursing, washing, mending, and doctoring.” This system became scandalous at the beginning of the 19th century; the insane were placed with the paupers. Those who agreed to take care of them often abandoned their contract with the town, and it was not uncommon to see demented persons wandering about in what was described as a “terror to the inhabitants.”

In 1816 the town purchased land from Andrew Capen for the purpose of uniting with Stoughton and Sharon to build a common almshouse. The poor refused to go to this newly established place and the plan was abandoned. Attempts to sell the property failed for several years, whereupon the surplus revenue was used to purchase a large farm on present-day Pleasant and Sherman streets. This was formerly the farm of Roger Sherman and in 1837 it became the Canton Almshouse.

The Poor Farm, as it became known, survived alongside the continuation of having some poor taken care of within individual homes. By the late 1800s the farm became a horrible and wretched place. The inspector of charities began a condemnation process in 1885. And yet the farm continued to house “inmates,” as the poor were classified. The report written by the commonwealth in 1887 paints a bleak picture. The inspector wrote, “Of these which are most uninhabitable I name Wayland as the poorest, then West Brookfield, Canton and Charlemont.”

The description is horrid: “The chambers on the second floor of the old building occupied as sleeping rooms by men contain each from one to four beds none of them in perfect order. Most of the bedsteads were old fashioned wooden ones bearing evidence of vermin. The beds were of straw and generously supplied with bedding which varied in cleanliness and order according to the habits of their occupants. Some I saw lying upon them in their heavy boots and clothing. In the women’s room the bedding lay in a tumbled heap. One room which was occupied by a young man in the last stages of pulmonary consumption who had come to the almshouse to die was particularly comfortless and wretched. The beds and bedding were in worse condition than in any other part of the house I saw vermin upon both. There was one for every cranny in the wall. I saw them crawling over the clothing of a deaf mute and the Superintendent assured me that a quart of the vermin could be collected in the old part of the house. What care this room receives is bestowed by the men who occupy it one of whom is eighty-one years old. None of the rooms are adequately supplied with means for heating them and in extreme weather there must be much suffering for only two have stoves of any sort. I was told that the inmates change their underclothing once a week and that their sheets and pillow cases are infrequently changed. Bathing among the inmates must be counted among the lost arts. There is not the slightest convenience in any part of the house for a full bath. When I asked the attending physician of the almshouse how frequently the inmates were bathed he replied: ‘The women are required to take a bath upon entering, the men at birth and when they are laid out.’”

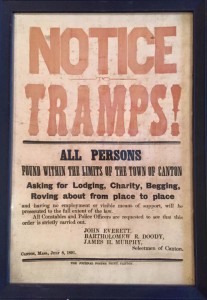

An 1891 poster warning tramps found roving through Canton (Collection of the Canton Historical Society)

The report went on to describe rotted boards, decayed vegetables, and poor ventilation. In short, it was a hellacious place to live and, ultimately, to die. The town, moved by the report, took on the responsibility of finding a new place for the poor. In 1887 a new farm was established on Walpole Street at what was historically the Kollock Farm. There was a fully stocked pond where trout had been sold for market. The farm contained 40 acres of land, access to a natural spring, and steam heat with bathtubs and toilets. There were a dozen bedrooms and plans for an addition. A special appropriation was raised and the town moved forward quickly. Renovations exceeded $13,000 — quite a sum at the time. The superintendent was paid $500 a year to oversee the place to maintain order and cleanliness.

The change was dramatic. The new farm boasted a reading and smoking room for the men. An ample sunny kitchen hosted the women, with a pantry and “cozy dining room.” On the day one visitor arrived he noted that he witnessed “fresh baking of the sweetest bread with rich brown crust that made us wish we would be invited to dinner.” More than 50 loaves of bread were baked each week using up more than 30 barrels of flour a year. In one season the farm produced 425 bushels of potatoes and in winter they harvested 60 tons of ice from the pond on site. In any given year there were 132 chickens, 14 geese, two pigs, four cows, and two calves as well as a few horses for working the fields. More than 60 cords of wood were gathered on nearby land to keep the building warm in the winter.

A follow-up visit by the Department of Charities reported that, “Excellent management prevails at this almshouse, both within the house and on the farm. There is partial separation of the sexes by day, and complete separation by night and at meals.” And much of the credit went to Superintendent Albert F. Reynolds. A disciplined man, Reynolds dealt fairly and with care over his charges. Not to say it was an easy place to live, as Reynolds was a taskmaster. “When a hobo desires accommodation, he is allowed to ‘hit the wood pile or the road.’ These ‘gentlemen of the road’ during the cold nights are very promiscuous and the ‘Tramp House’ — a separate tenement for transients — has often accommodated 22 at one time.” It was observed that Reynolds had hardened his heart towards vagrants and insisted they work before being fed and they were often referred to as “Weary Willies.”

The final observations of the Poor Farm were described as the grounds of a well-kept summer resort: “This pleasant home for the indigent poor … looks so neat and picturesque. The drives lined with neat stone gutters and walks with borders of compactly placed rocks as spotless white as though newly washed.” Canton, after close to 200 years of failing the poor and most helpless, had finally done the right thing. The Almshouse on Walpole Street was used for 35 years and closed in 1922. Today, portions of the farm are now Knob Hill Estates, where homes are valued at close to $800,000 each — a far cry from poverty.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=38443