True Tales from Canton’s Past: Honor Village

By George T. ComeauEmblazoned on the back of the Ford truck rattling through Canton Center is a bumper sticker that reads “Support Our Troops.” And in Canton, we are most fortunate to have a veterans agent who has worked for years to raise the status of our troops such that it is a no-brainer when it comes to helping our men and women as they transition from the military back into civilian life.

The Honor Village was conceived as a cooperative experiment in providing housing for returning veterans of World War II.

It was not always the case that our town unequivocally supported the needs of soldiers returning from battle. One glaring case stands in our history that serves as the all-time winning example of “Nimby-ism” — that being full support unless of course that support means that something will be built in “my backyard.” In the days that followed the end of World War II, the men from Canton returned to a town that had changed greatly over the course of the American portion of the four-year conflict.

Most notably, Canton was becoming a town in which property values and affordability continued to exceed income levels, especially for young men upon return. A wealthy industrialist and U.S. Navy veteran of World War I by the name of Tobe Deutschmann came up with one solution: He would create a lottery to sell house lots to veterans that were valued at $1,000 each for $1 a piece. It would be an idea that grew much larger as the plan developed.

Tobe Deutschmann was raised in Dorchester by German immigrant parents. At a very young age he distinguished himself in the field of avionics and radar. An early European trip in 1927 gave him amazing insights into the fledgling field. For three months, he studied radio communications as they applied to aircraft, and in doing so most of his time during that vacation was spent in the air. Friends who joined him on that trip nicknamed him the “Flying Deutschmann.”

Deutschmann became quite successful after moving his electronics firm from Cambridge to Canton, where he purchased the factory on Washington Street that was once the Rising Sun Stove Polish Company. Developing special resistors and transistors, he made critical communications breakthroughs that allowed for the invention of a filtering device that suppressed static during radio operations. Early devices were installed in tanks opposing the Germans in Africa, and later they were installed in all aircraft and jeeps as well as key Army vehicles.

Although a German by heritage, any question of Deutschman’s allegiance was dispelled when, in September 1942, the Ponkapoag resident participated in the Canton Days Rally. A German helmet that had been riddled with holes by an American machine gun in World War I was placed up for auction. It was Deutschmann who placed a bid for the $50,000 war bond to purchase the helmet. As 7,000 of Canton’s citizens looked on, Deutschmann announced he would melt the helmet down and return it to Hitler as “little death dealing bullets.” Continuing, he expressed in no uncertain terms why winning the war was an imperative: “We must make every sacrifice; our effort is by no means complete. We must do more.”

After the war ended, droves of men returned to Canton. Deutschmann was heard to remark that he wanted to shame the people of Canton into doing more for the veterans. “I got tired of hearing all these people talk about getting land and homes for veterans and then going home and forgetting all about it.” Putting his money where his mouth was, he purchased a large lot of land on the corner of Dedham and Elm streets and publicly announced at the annual town meeting in 1946 that the first 18 Canton veterans who contacted him could have a $1,000 house lot for $1 each. More than 150 men immediately applied, hundreds phoned, and close to 30 physically came to his house, some even on crutches.

The 1947 annual town meeting was chaos. The Boston Globe described it as the “largest and most confusing meeting in town history.” Town meeting was scheduled to begin at 8 p.m., but by 6:30 that night Memorial Hall was packed to the rafters. Over 1,000 people jammed the room and people had to sit on the stage. The controversy was over whether to change the town’s zoning bylaw to reduce the size of buildable lots from 40,000 square feet to 15,000 square feet. At the time, the zoning map showed more than 85 percent of the town as Class A, and a local citizen brought forth an amendment to reduce the lot sizes. Veterans could not afford to pay for or develop such large lots.

Deutschmann pressed forward at that town meeting and called the zoning laws “a stone around the neck of the town,” and urged voters to allow veterans the ability to build homes. Heckling and catcalls ensued and the whole evening devolved until it was adjourned at 11:30 p.m. with the veterans losing the zoning change by a handful of votes. A week later, the veterans packed the hall and reversed previous zoning bylaws and land was rezoned to create a Class C size of 6,500-square-foot lots. Deutschmann and his friends won the day, and his plan moved forward.

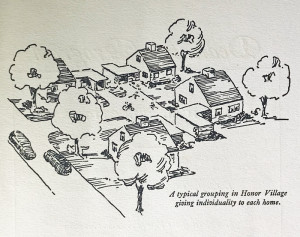

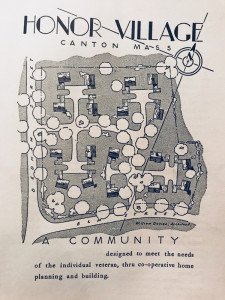

On Saturday, August 24, 1946, at 10:30 a.m., more than 800 people gathered at the cleared land that would become known as the Honor Village. John Pesaturo from Canton and Mr. Sansone from Norwood sent buses throughout the town so that anyone could attend. A 24-foot spit was constructed and five steers were roasted along with 1,000 ears of corn. Children played games and ice cream cooled the hot summer day. Deutschmann explained that on the home sites the dwellings would be arranged in a village fashion, allowing for privacy not usually afforded in the “usual rows in ordinary low-cost development.” William Davies, a noted architect, donated blueprints for $1 per house. “If Deutschmann can let his lots go for a buck, I can’t see where I can charge any more for my drawings,” he said.

The chairman of the Board of Selectmen, Carlton Tabor, spoke to the crowd with the hopes that this project would be the start of additional and much-needed veteran housing opportunities. When it came time to raise the flag, Rene Gagnon from Manchester, New Hampshire, performed the honors. Gagnon was one of the men pictured in the historic photo raising the American flag on Iwo Jima. When the time came to draw the names, all eyes turned to Charlie Tolias of Mechanic Street. Confined to a wheelchair as a result of his war injuries, this war hero was selected to draw the 18 names. All the names were in sealed capsules, and on the ninth selection, Tolias drew his own name. And at the end, Deutschmann had one more surprise: he awarded a 19th lot to Frank Brown of Pond Street.

It seemed like a utopian answer to the housing shortage. The only catch to the whole enterprise was that each veteran had to build a home on the lot. The idea was that they could build a home at $6,500 each if they all participated in a co-operative venture and all built at once. In a 14-page book, the outline for the Honor Village was born. Deutschmann held up his end of the bargain, yet by 1953 not a single house was built, and several veterans sued for a deed transfer so they could sell the valuable land. A court case ensued and Deutschmann explained that “the Board of Selectmen had the deeds for a year and a half and then returned them,” adding that “the men did not want to build.”

In the end, the homes were never built, but zoning laws did change, and subdivisions in Ponkapoag and along Dedham Street took advantage of the change in lot sizes and a building boom ensued. Many of the small post-war slab houses were built as a result of that pivotal town meeting. The Honor Village stood as a symbol for the creation of a very different Canton, that in which zoning played a key role in the development of a much denser community. Deutschmann went on to be a founder of Radio Shack, but his utopian ideals were clear. Honor Village is a concept of “richer living facilities placed within reach of citizens having but moderate means. It is an expression of the pioneering spirit that built America. It is a means of preserving the American home — the foundation of our civilization!” Indeed, it would have been great to see.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=37732