True Tales from Canton’s Past: Dividing Lines

By George T. ComeauWe have this strange attraction to thinking that this is our land. We place fences and markers and boundaries upon our property. We feel aggrieved when a neighbor walks across our land. We feel that it is right to stop others from incursion, only after we ourselves have incurred. And through the ages there is one constant — that being the fact that when we, as white settlers, arrived here in the “New World,” our ancestors set forth to place their laws and beliefs upon the native population and thereby created a foreign concept in land ownership.

The land we now call Canton has a history that can be traced back more than 15,000 years. The fact that man lived, worked, and died here is well recorded in the archeology of this place. But modern concepts of ownership really began taking shape in 1637. This was once a majestic forest, rivers teemed with fish and fowl, and the only roads were well-worn footpaths. Incredibly, some of the the same footpaths that existed in the 1620s and before are still evident today if one knows where to look and has a keen understanding of the topography.

There are rocky outcroppings, large boulders, pot holes, eskers, and kettle holes that have been here for thousands of years and remain unchanged even by human hands. There is awe in a hike through the Fowl Meadows at the topography that can be be seen through eyes that glance back thousands of years into our history. And yet the original land is largely changed today through hundreds of years of deeds and transfers.

The native chief Chicataubet seemingly allowed the “occupancy of Dorchester” in 1630, and by 1633 he was dead at the hands of smallpox. By 1644, Josias, a successor to Chicataubet, submitted to the English government, and all was set in motion for land ownership in this area. Kitchamakin, a brother of Chicataubet, wound up signing over the “land beyond Neponsit Mill, and unto the utmost extent” to the English. This was understood to such enlarge Dorchester, which had at the time only extended to the top of the Great Blue Hill. That deed in 1637 made Dorchester the largest town in New England.

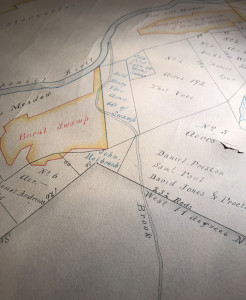

To place the deed of 1637 in context, the land encompassed everything between the Blue Hill to the Plymouth line. It was an enormous tract containing over 42,000 acres of land and 900 acres of cedar swamps and 1,100 acres of meadows. It became known colloquially as the land “beyond the Blue Hills.” In 1707 it became known as the “New Grant.” In order to facilitate orderly ownership and clean division, a select group of men became the proprietors and laid the area out into divisions of parallel lines running from north to south. This became known as the “Twelve Divisions.” Marginal land such as wetland, lowland, and swamps were excluded and a rule of proportion was made such that 480 proprietors were named and each was given a proportionate share of land.

In some cases, the named proprietor never even set foot on his land; in many cases it was the children who would live and expand upon the property in the wilderness. And in order to provide for the spiritual guidance of these people, the proprietors split a total of 400 acres of land in two, and half went to the ministry on the northwest side of the Neponset River and the other half on the southeast side. Seventy-five acres was further given free and clear to the first minster who would settle and remain with the settlers for a period of 10 years. For those individuals who had claims on land, the setting off by the proprietors was a windfall.

In essence, if you lived on a piece of property and had a deed or freehold from the natives, then the government through the scheme of the laying out of the divisions set off 12 times the amount of land that you already owned. A map was made, drawn by John Butcher, and was called the “Map of the Twelve Divisions,” whereby each lot was numbered and apportioned to a different settler. By 1711 a second map was drawn by James Blake and called the “Map of the Twenty-Five Divisions,” further dividing even more of the land.

Blake was hailed as an ingenious mathematician and for his time a most accurate surveyor. A selectman of Dorchester, Blake wrote a book entitled Blake’s Annals of Dorchester, which is one of the most important early histories of the people and places of this area. As for the mapping of this area, one local historian wrote, “Imagine if you can, trudging through unbroken forests with no guide other than the needle of the compass. The measurements were links and chains, not in feet, and one hundred links made a chain which was sixty-six feet long.”

At the top of the map a verse was inscribed that alluded to the difficulty of creating a map of this territory that began in 1711. “Upon our Needle we depend, In ye thick Woods our course it know. Then after it ye chain Extend, for we must gain our distance so. Over ye Hills through brushy Plains, and Tedious Swamps where is no track, Crost Rivers, Brooks we with much Pains, Are forced to travail forth and back.” The poem continues for several more stanzas, before ending with the words “May we our Generations serve, According to God’s holy Will, and from his Precepts never Swerve, Labour to do our Duty Still.”

The work of the map was completed in 1730 and took over 14 years to complete. What was demarcated was the land owned by the “Dorchester Proprietors” and encompassed the land now known as Stoughton, Sharon, and Canton. A series of small freeholds emerged through the sale of portions of these lands. Huntoon, our early historian, wrote that “thus was created a love of freedom, and a capacity of self-government developed, which was in after years to bear a rich and abundant fruit.”

Today, almost all of the land and boundaries can be traced back to the “Map of the Twenty-Five Divisions” and in one case, there is an intact piece of property that has been unchanged in shape and boundary since 1707 when the natives gave access to a small piece of land to the English which was within their Plantation. As you travel towards Ponkapoag on Washington Street there is a small cemetery on your right. It is known as the Olde English Burying Ground. It is the small graveyard on a hill. It is actually two cemeteries. On the top of the hill is the “Proprietor’s Burying Ground” where between 1690 and 1716 our settlers were buried. The actual deed to this place was procured in 1741 for £5 and encompasses one quarter of an acre.

After hundreds of years, the proprietors still have managed to hold onto one piece of the land they divided. In this small resting place are the men that shaped the land on which you now live and can trace your deed back to the creation of this place we call Canton.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=35613