True Tales from Canton’s Past: Under Three Flags

By George T. Comeau

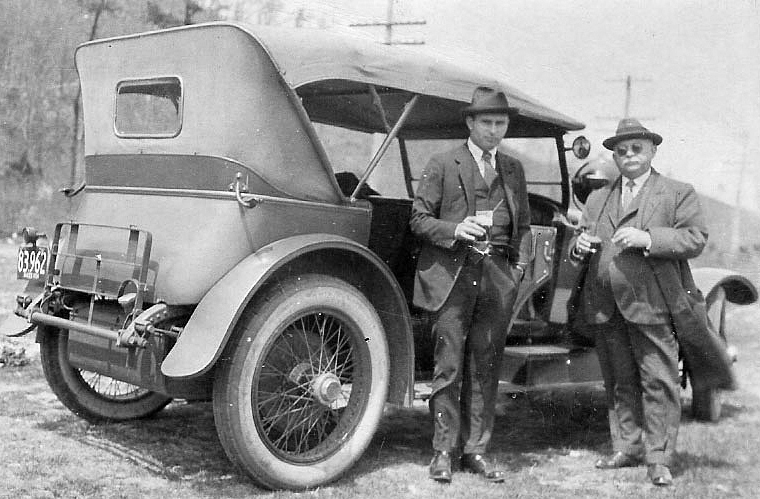

John Meyer and Hans Krauß, likely in Canton in 1919 (Courtesy of Anneliese Neumann)

As the mail arrived at the town clerk’s office, one letter stood apart from the rest. The dispatch was postmarked from a small Bavarian village. And as Gail McHugo slit open the envelope, a simple typed note began a journey into Canton’s history that few know about today.

“More than 100 years ago,” the letter began, “a man came from our village to Canton, his name was John Meyer.” The writer was a distant relative who was a local historian working on a chronicle of the place in which Meyer was born. To this day there are examples of Meyer’s generosity in his hometown. Meyer paid for the World War I memorial in the village of his birthplace, and he also donated the bells that still ring out in the Lutheran church steeple in Etzenricht. Back in Germany there are vestiges of the philanthropy of this man from Canton, and until last week the record was silent.

Today, here in town, not a single soul knows the story of Meyer, but his contributions to the U.S. military are still felt today. The khaki cloth that our soldiers wear, the heavy cloth of the tents, the sails of historic yachts — all connected to Canton. This is a story of a remarkable man who held citizenship in three countries, and Canton was his home, and the place in which he made his fortune.

John Henry Meyer was born in Bavaria in 1857, and at age 14 he was sent to live in England to be privately tutored. Most of his teenage years were spent in Yorkshire, which was the center of textile production. There is no doubt that Meyer grew up at the point where the industrialization of mammoth mills was altering the manufacturing landscape in England. Meyer spent time learning all aspects of the export trade and traveled extensively to all of the world’s greatest business centers. Perhaps his greatest experiences were in the bazaars of the East Indies. Flowing fabrics, richly dyed cloths, and exotic ancient weaves were all part of Meyer’s education in textiles.

In 1893 a panic in the markets caused a worldwide shift in financing and resulted in the collapse of hundreds of banks and thousands of businesses. The “silver exchange” in the United States was partly to blame for the global depression, and Meyer was forced to return to England from the Far East and cancel his trade missions. Soon, however, Meyer became the first English manufacturer to ship to America heavy wool cloth that would be dyed and finished in America.

Meyer had married Annie Wadsworth, the daughter of a wealthy family whose name was synonymous with textiles in the region. By 1895 the Meyer family, consisting of John and Annie along with their four children, boarded the White Star Line’s S.S. Germanic at Liverpool, England, and crossed to New York City. There were 514 passengers in steerage on that voyage, yet the Meyer family traveled in their own cabin, owing to their wealth and prestige. Upon arrival in New York, the family settled in Brooklyn, and by 1909 they lived at a luxury Central Park West address with two servants.

The wealth of the Meyer family was deeply rooted in the connection to Canton, and he became a citizen in 1902. In September 1903, Meyer, along with a few partners, bought the land and buildings in the Springdale section of town. By 1919, Meyer also employed at least one German relative named Hans Krauß to be his plant superintendent at Springdale. The land that Meyer developed was situated between Pine and Bolivar streets, and modern apartments and condominiums have long replaced what was the Springdale Finishing Company. Under the ownership of Meyer, this new factory would become the largest supplier of khaki to the U.S. military, the lion’s share of which was produced right along the artificial pond, which helped wash away the wastes.

Before Meyer even came to Canton, his fortune was secure. The growth of Meyer’s industry began with the outbreak of the Spanish-American War when he was the only person in the United States who could furnish the cloth for the uniforms in the particular mineral dye in the color of khaki. There were other mills, but they used an inferior sulphur-dyed process in which the fabrics had a tendency to fade and become discolored. The conflict in 1898 was the first in which the color of the uniforms was consistent and standard. There were no variations in the khaki color, which was a color adopted by the British as early as 1868, and of course was standard for troops in India as early as 1848.

At the center of developing khaki in America was Meyer. Within a few years he was not only producing uniform cloth, but also tents and sails. The U.S. government turned to Meyer to produce the standard for the cloth. The flagship Olympia commanded by Admiral Dewey was fitted in cloth duck made by Meyer, and he supplied the U.S. Army with shirt cloth for several years.

In all, Meyer owned six mills spread across Massachusetts and Pennsylvania. The mother of all mills was at Springdale in Canton — the flagship plant for the corporation. The company was massive and employed hundreds of men. One newspaper article pointed out that the work “is too hard for women.” The process required the use of bleach and sulfur and immense boilers. The procedure has been likened to developing a photograph. Canvas was bleached for 24 hours and then “mangled” through enormous wringers and dried between heated cylinders. Long strips would be painted and then dried through a steam process, developing the specific color through subsequent dyes and paints and chemical pigments. There is no doubt that the plants at Springdale used insidious chemicals to achieve the finished product, and at the same time the waste was flooded into the streams and rivers as runoff from the plant.

In 1916 on a single day, more than 150,000 gallons of putrid, chemically laden waste flowed from the Springdale Plant. That amounted to 39 million gallons a year at the height of the operation. It was a sickening smell and the work was dangerous. And yet Meyer’s industrialization of the process made him the largest manufacturer of khaki cloth in the country. Year after year there are records of the industrial waste that flowed from the plant, yet in wartime there were few actionable complaints due to the great need for the products being produced.

By the time World War I was in full swing, Springdale Finishing Company was producing the tents for the American forces. The cloth made here in our town sheltered some of our very own boys from Canton. Meanwhile, the cloth was also being produced for our allies. The government contracts were so huge that Congress held hearings on the bid process and inspectors faulted the plants for their inability to maintain proper inventories. Meyer maintained offices in Washington, D.C., as well as New York City to keep up with the demand for his khaki cloth.

It must have been a difficult time for Meyer — a German by birth yet now an American citizen with the world at war with Germany. A letter written in 1917 to the secretary of state in Washington outlined the concern that the company had with fulfilling contracts with firms in South America that had German citizens as owners. Meyer was clear: “We wish to in every way, assist, aid and carry out every regulation or law or rule or request of our Government.”

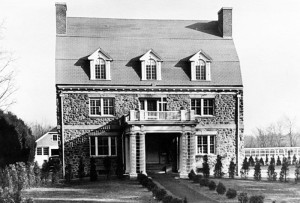

In 1909, Meyer purchased several acres of land on Pleasant Street that today is the site of the Senior Center and the Chapelgate subdivision. This large tract of land would become his Canton estate. And though he lived in New York, he also spent vast amounts of time here with his family. The house he built was a massive stone mansion with 15 rooms, five tile baths, a caretaker’s cottage, an extensive orchard and garden, and uncommon for the time, a three-car garage. It had the sense of an English manor and was quite luxurious. Meyer died in Canton on November 30, 1926. Annie, his wife, died less than two months later. Both husband and wife were buried in Kensico Cemetery in the Hamlet of Valhalla, Westchester County, New York.

Today, whenever you see a khaki uniform, think of John H. Meyer and the empire he built from Canton.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=32249