True Tales from Canton’s Past: Sword of a Hero

By George T. ComeauUnder the light of a dim moon, on the southern bank of the Rio Grande, the brigadier general known as “Old Rough and Ready” hastily wrote a letter to his son-in-law. The days had been filled with battle, and victory was in the hands of Zachary Taylor. He wrote, “So brilliant an achievement could not be expected without heavy loss on our side, we have many killed and wounded, among the latter is … Lt. Gates, Jordan, Selden & Burbank & some others besides many non commissioned officers and privates.” And in that battle on May 9, 1846, lay wounded one of Canton’s most illustrious and forgotten heroes: Charles D. Jordan.

Charles Downes Jordan was born in Canton in 1820. His uncle was Commodore John Downes, one of the highest-ranking officers in the U.S. Navy. It is likely that Downes helped pave the way for his nephew to attend the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Graduating from a class of 56 cadets at age 22, Jordan began a lifetime of military service. Upon graduation from West Point, he was promoted to the rank of brevet second lieutenant, 8th Infantry.

Jordan spent his first three years of military life in rural forts in Florida that had been established by the government to fight the Second Seminole War. The first assignment was Fort Shannon on the banks of the St. Johns River. Within a few months he was transferred to an enormous coastal fort then known as Fort Marion. Built by the Spanish in 1672, it had previously been known as Castillo de San Marcos and was a classic fort complete with strongholds, wet moats, earthworks, and four full bastions. At the time Jordan was stationed there, the fort was part of the U.S. Coastal Defense and considered a highly strategic asset of the U.S. Army.

By 1844, Jordan was transferred to the 8th Infantry and became part of the military occupation of Texas, leading him into the War with Mexico and to service in the forces under Zachary Taylor. The battles that Jordan would join were bloody and graphic, involving hand-to-hand survival or death. The Invasion of Mexico was the fourth of five major wars fought on American soil.

General Taylor had been sent to Mexico in anticipation of the annexation of the Republic of Texas, which had established independence in 1836. Taylor was ordered to guard against any attempts by Mexico to reclaim the territory. By July 1845, when annexation became imminent, President James K. Polk directed him to provoke the Mexicans and “deploy into disputed territory in Texas, on or near the Rio Grande” near Mexico. Taylor chose a spot at Corpus Christi, and his Army of Occupation encamped there until the following spring in anticipation of a Mexican attack. The battles that ensued became known as the Mexican-American War.

This was the war in which the telegraph updated people with the latest news from the front. This was the first time in American history that accounts by journalists had great influence in shaping people’s opinions and attitudes toward a war. Jordan fought at the Battle of Palo Alto on May 8, 1846. News about Taylor’s victory at Palo Alto brought out large celebratory crowds in places such as Lowell, and torchlight parades were held in New York City.

Yet Charles Jordan was likely not celebrating — it had been a bloody day for both sides. The battle took place on disputed ground about five miles from present-day Brownsville, Texas. A force of some 3,700 Mexican troops — a portion of the Army of the North — led by General Mariano Arista engaged a force of approximately 2,300 U.S. troops led by Taylor. When fighting ended as twilight fell, Mexico had lost 102 men with another 129 wounded, and the American Army lost four men, with 48 wounded. While the victory was decisive, the next day would be even bloodier for both sides.

The Mexican Army had moved overnight to a more defensible position along an old meandering river bed known to the Americans as Resaca de la Palma. It was here, along the 12-foot-deep and 200-foot-wide ravine, that the battle took place. At 3 p.m. Lieutenant Jordan, almost 2,000 miles away from home, stood with his comrades in a life-or-death battle. The fighting was disorganized and uncoordinated due to the dense chaparral and the intense Mexican artillery fire. The Mexicans had over 4,000 soldiers while the Americans had a force of 1,700.

Taylor writes of both battles the next day, “After a severe affair of yesterday, principally with artillery, with six thousand of the best Mexican troops we succeeded after a continued contest of five hours in driving the enemy from his position and occupying the same laying on our arms; at day light he was still in sight, apparently disposed to renew the contest … we commenced about four o’clock P.M. & after a severe contest of two hours at close quarters we succeeded in gaining a complete victory, dispersing them in every direction and taking their artillery, baggage, or means of transportation … the enemy who escaped having recrossed said river.”

Jordan was among the more than 89 men who fell wounded that day. He was not among the 33 killed, yet his wounds were certainly serious. That same day, as he lay on the field severely wounded, Jordan received a field promotion to the rank of first lieutenant for “Gallant and Meritorious Conduct in the Battles of Palo Alto and Resaca-de-la Palma, Texas.” It is likely that Jordan was sent to recuperate at Fort Hamilton, just outside New York City Harbor. It was here that fellow Canton citizens joined up to celebrate the young hero.

Jordan’s friends had closely followed news of the victories. At the house of Canton native George Endicott, a wealthy and prominent lithographer, Jordan was presented with a ceremonial sword as a “testimony of regard, and of admiration for his gallantry.” As the men and women looked on, Major General Charles W. Sandford presented the sword to the son of Canton. Looking on that evening was the American painter Asher Durand, along with dozens of other luminaries who came to celebrate a war hero. “Lieut. Jordan replied in a very modest manner to Major General Sandford. He said he was taken a little by surprise in the presentation of the sword, but it was a soldier’s duty to be always ready.”

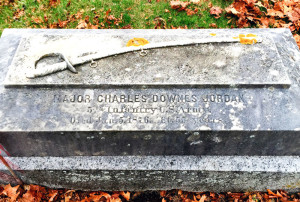

Charles D. Jordan’s grave at Canton Corner Cemetery, adorned with a battle sword (Courtesy of the author)

Jordan felt that he had done no more than his duty, and considered it a “favorable circumstance to have been wounded,” as it excited the sympathies of his countrymen.

It was Endicott who put the hero in perspective. “The favorable circumstances was his having three gun shot wounds in the arm, two in the breast, and two bayonet stabs in the back!” Endicott exclaimed, adding, “Jordan was some distance ahead of his company when he charged upon the enemy, and when he fell he was pinned to the ground by a bayonet in the hands of a Mexican, and would have been killed, had it not been for the bravery of Lieut. Lincoln, a son of Governor Lincoln, of Massachusetts who came to his rescue and with his own sword slew the two Mexicans who were about despatching Lieut. Jordan.”

Jordan returned to the war and was at the bloody Siege of Vera Cruz and the Battle of Cerro Gordo. After the war, he remained in Texas and served at several forts and garrisons until 1861, when he was captured during the early days of the U.S. Civil War. On March 20, 1861, Jordan was evacuated from Fort Duncan as the Confederacy took control of the Union garrison. At that time he was considered captured and promptly paroled as a prisoner of war. Returning home to live with his mother, sister, and extended family on Pleasant Street, Jordan was likely out of place in the feminine household. The house, known as the Jordan House, was bought by Commodore Downes for his sister and became home to several women, including Laura Revere, wife of Edward H.R. Revere. The grandson of Paul Revere, Edward, a field surgeon, died tragically in the War of the Rebellion at Antietam in 1862.

In 1863, Jordan retired from military service as a result of “disability and disease in the line of duty.” With a long and faithful career, it is likely that no other soldier from Canton has ever seen as many battles and conflicts in their lifetime. On January 5, 1876, he died and was buried at Canton Corner. Having served in the Seminole, Mexican, and Civil War, appropriately atop his grave is an engraved sword — a connecting point to the many battles and bravery and the hardships he most certainly endured. In 1914, Jordan’s surviving family received $1,627 as a result of a U.S. Supreme Court case in which longevity pay was awarded for incorrect calculations made by the Army in failing to account for years as a West Point cadet. It is likely that Jordan would have hardly cared; he was a soldier and simply “did no more than his duty.”

Special thanks, as always, to fellow curator Jim Roache for his intrepid research and support in digging up the old dirt.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=29297