True Tales from Canton’s Past: Copper Mill

By George T. ComeauAs an old and distinguished man, he had earned a well-deserved rest in the autumn of his life. Yet Paul Revere was not like his contemporaries of the day; throughout his life he remained driven and entrepreneurial. And at age 65, he was about to undertake his most ambitious project yet. He needed a secure and large tract of land, access to power and labor, and the confidence of the Unites States government to back his idea. Innovation born from the American Revolution is at the heart of Revere’s quest to become the first American to perfect both the art and the science of manufacturing rolled copper.

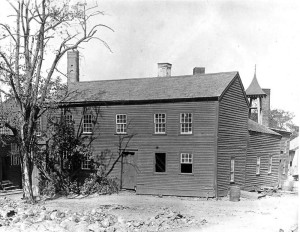

The house in Canton that Paul Revere lived in between 1801 and 1818 (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

In early life, Revere had distinguished himself as a master silversmith. At the age of 21, a youthful Revere began running his father’s silversmith shop in what is now Boston’s North End. The work produced from that small shop was diverse, artistic, and of the highest quality — a hallmark that would endure throughout Revere’s life. Much of the life of the patriot is well covered in history and literature as well as folklore. Yet the basis for his industrial knowledge was furthered when in November 1775 the Continental Congress sent Revere to Philadelphia to learn how to manufacture gunpowder — so vital to the colonial cause.

While Revere was on his mission in Philadelphia, the House of Representatives appointed a committee to consider the proper place to erect a powder mill. An established mill in that part of Stoughton that is now Canton was considered, as well as sites in Andover and Sutton. Stoughton had the edge over the competitors, and the site owned by Samuel Briggs and his son was selected. On February 20, 1776, the land that now borders the vicinity of Plymouth and Neponset streets was purchased by the Colony of Massachusetts Bay for £100 and included three quarters of an acre of land, part upland and part mill pond. A committee was ordered to “commence the building of the mill at Stoughton, and to exert themselves to hurry on this important and necessary business without delay.”

Upon Revere’s return, he was responsible for supervising the construction of this powder mill. Once completed, the mill was run by Major Thomas Crane, who, along with Daniel Vose, were both paid handsomely for their efforts in building and running the military installation. By May 3, an issue of the Massachusetts Spy reported, “The powder mill at Stoughton will begin to go in a few days.” Once established, the building was surrounded by a high post and rail fence, behind which a 24-hour guard was placed with orders from the colonial government to “fire upon any persons who shall attempt, upon being three times forbid by such guards, to enter the said lines.”

By all accounts, the enterprise at the mill was amazingly successful. Within months the output totaled more than 40,000 pounds of powder. A writer of the time reported that the powder “was of excellent quality.” By this time, Paul Revere was the commanding officer of “the Castle” in Boston and took large quantities of powder for the defense of Boston Harbor. After the war, in 1779, the mill was sold to Samuel Osgood with the express condition that during the succeeding four years he be obliged to manufacture for the state all the gunpowder needed, provided the request did not exceed the capacity of the mill. The state provided the materials, and the new owner was compensated a portion for the manufacturing process. But the promise to the state was not to be realized, because on October 30, 1779, the powder mill at Canton was “blown to atoms.” The explosion was as expected — horrific. Benjamin Pettingill, then 31 years old, was “very much burnt” and died 35 hours later. The mill was not rebuilt and the millstones that had been used to grind the powder were bought by General Richard Gridley and relocated to a small mill on Washington Street near Shepard’s Pond.

After the revolution, Revere set to casting bells, housewares, and most importantly, brass cannons for Massachusetts. The experience and contacts during the war gave him an advantage over other contractors, and his early contracts included over 40 pieces for Massachusetts and Virginia. In 1794, Revere worked with his friend, Henry Knox, who was then George Washington’s secretary of war. Having such a friend in a high place allowed Revere to receive a contract for brass howitzers for the federal government. This was a turning point for Revere, both in terms of working with the government and also his interest in copper and brass. The materials furnished by the Unites States for these cannons were inferior, and Revere knew he needed to secure a better and improved way to manage the metallurgical process for handling copper.

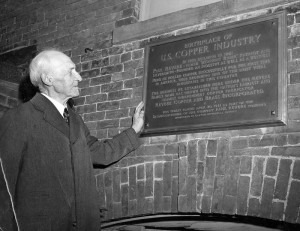

Edward H. R. Revere, the great-grandson of Paul Revere at the plaque dedication of the rolling mill on April 20, 1951 (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

The late 1700s saw a huge build-out for both military and maritime commerce. Copper sheeting was used to prolong the quality and usefulness of large ships. British copper was imported in large quantities, protected by low tariffs. By 1798 a major English copper mine failed, and this was compounded by extensive losses born by the British Navy during the war with France. Revere was the first to declare that America needed a domestic source for high quality sheet copper. For the next several years, Revere perfected the process of hardening copper for maritime use such that his product far exceeded the quality of his competitors. Like all entrepreneurs, Revere had the innate ability to build upon his previous successes and failures to innovate and create.

In 1799, an issue of the Massachusetts Mercury reported that the Frigate “Boston” was the first ship whose copper bolts and spikes were exclusively manufactured in the United States. “We think the publick are under obligation to PAUL REVERE, Esq., for his indefatigable attention to this Branch of Naval Architecture, especially at a time when the British Government has prohibited the exportation of that valuable article.”

Revere was intimately familiar with Canton, the people, and the water privileges upon which the mills depended. And it was here that Revere turned to find the location to build a new empire in industrial manufacturing of copper, brass and other metals that would transform the country in both war and peace. On March 14, 1801, Revere purchased the mill site on which he had supervised the construction of the colonial powder mill. Standing on the ground at the time were a small dwelling house, a trip-hammer, and a “cole” house. Revere purchased the mill from Messrs. Robbins, Leonard and Kinsley.

Already, Canton had become home to some very prosperous mills. Leonard and Kinsley had already operated a small slitting mill on this very property and owned substantial property upstream in what is now Canton Center. Revere was able to renovate some of the existing equipment and spent $6,000 to purchase the site along with some of the use of the water that flowed through the mill. Within several months, Revere was leveraging his fortune and placing great resources in the mill at Canton. Water-powered trip hammers crushed raw iron ore, air furnaces smelted the product, and molten copper was drained into flat bar-shaped molds and further refined through hand hammering. Finally, the bars were heated and passed through rollers, successively decreasing the thickness until sheets of copper were produced.

The earliest years of Revere’s factory in Canton were plagued by severe financial shortages as a result of a federal government that was slow to promise, slow to pay, and politically averse to contracting with private citizens. One saving grace came in October 1802, when the commonwealth of Massachusetts purchased over 6,000 feet of rolled copper weighing over 7,675 pounds, along with almost 800 pounds of copper nails to cover the dome of the state house. Revere avoided bankruptcy when the $4,232 payment arrived in time to fulfill some of his extensive debts. The contracts for materials involving state projects always seemed to flow effortlessly, as opposed to the U.S. Navy contracts, which suffered long and laborious payment terms.

Within a few years, the business began to prosper, largely as a result of enormous government contracts that flowed smoother as a result of the quality and quantity that Revere was able to produce at Canton. The company ledger books include the sale of cannons, copper bolts, spikes, sheeting, as well as engraved silver and some of the finest bells cast in America.

Robert Martello, a Revere biographer who specializes in industrial history, wrote, “In post-revolutionary America, no one could guarantee success, particularly in such a secretive, complex, and cutting-edge field. Revere began this last ride of his own volition, and risked everything he had in it. Victory would belong to himself, his family, the Navy, and the nation, but defeat would rest on his shoulders alone.”

The mill at Canton was indeed a victory for not only Paul Revere, but for the nation as well. And in 1801, as Revere moved into the small house on the site of the mill, he also began what would become an almost two decade relationship with a home he would call Canton Dale.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=28749