True Tales from Canton’s Past: Dear Children

By George T. ComeauThe imagery that stirs the loudest in the Ken Burns documentary The Civil War is that of the letter from Sullivan Ballou to his wife, Sarah. In his now-famous letter to his wife, Ballou endeavored to express the emotions he was feeling: worry, fear, guilt, sadness, and most importantly, the pull between his love for her and his sense of duty to the country. And that letter, now famous, is simply one in thousands upon thousands of letters home from our men and women in the military that express love, fear, and the emotions tied to war.

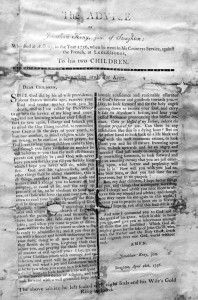

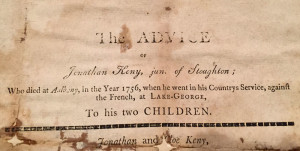

The advice of Jonathan Kiny Jr. to his children was published soon after the ensign’s death in 1756.

Letters home have always served as a reminder of the costs associated with great sacrifice. In fact, many of these letters became wartime propaganda, held up as an example of the glory of service to one’s country. In the effort to promote the Second World War, thousands of posters were created to “sell messages.” Federal agencies printed a downpour of brightly colored posters. Labor unions and factory owners printed up their own versions aimed at turning defense workers into “production soldiers.” At the end of the day it is emotion that moves the spirit to action. And while we may think propaganda is a modern invention, it is in fact an ancient art. If the letter home from Sullivan Ballou stands out, it is because the emotions are real, deep, and intensely personal.

More than 100 years earlier, the French and Indian War was the North American theater of the worldwide Seven Years’ War. The war was fought between the colonies of British America and New France, with both sides supported by military units from their parent countries of Great Britain and France, as well as native allies. As the war began, the French North American colonies had a population of roughly 60,000 compared to 2 million in the English North American colonies. The outnumbered French particularly depended on the Indians. Long in conflict, the two nations declared war on each other in 1756, escalating the war from a regional affair into an international conflict. This was the war that saw the expulsions of the Acadians from the Annapolis Basin in Nova Scotia and redrew the boundaries of two nations.

To bolster troops brought from England, the crown turned to the colonists as support for the war efforts. As early as 1744, Governor William Shirley devised a plan to take Louisburg. Several local militiamen were pressed into service for the king. Throughout the war, many Stoughton men took part in hostilities, and we have many examples of how the war changed lives right here in our own community. Guiding by example, the Reverend Samuel Dunbar was a staunch supporter of the crown. Dunbar was of the highest moral character and most esteemed by the entire community, so when the King of England placed the call of duty in 1755, Dunbar, as chaplain, accompanied Richard Gridley and Paul Revere (then 21) to fight against the French at Crown Point.

Crown Point was a critical and strategic battleground for the war between the two nations. During the 17th century, both France and Great Britain laid claim to the Champlain Valley — the French by virtue of the voyages of Verrazano, Cartier, and Champlain; the British based on those of the Cabots in 1497 and 1498. It was at Crown Point where 13 men from Stoughton would fall in service to the crown.

William Johnson was placed in command of a force of 3,500 Provincial troops from New England, New York, and New Jersey, for the expedition against Fort St. Frédéric. While the Provincial troops prevailed, they did not press their advantage.

In response, the French began construction in October 1755 of Carillon (later named Fort Ticonderoga) to serve as a buffer between the British position at Lake George and Fort St. Frédéric. During this period of the conflict, more than 30 young men from what was then Stoughton — but largely now Canton — fought in the war.

Col. Samuel Miller, whose military district included the town of Stoughton, said that in 1755 the town had 320 enlisted soldiers, that the stock of ammunition consisted only of four half-barrels of powder, and lead and flints accordingly, which was but half of what the town should possess. The selectmen accordingly ordered a tax of £40 to be assessed to make good on the deficiency.

The story of some of the Stoughton men who enlisted in his Majesty’s service in the expedition to Crown Point is wrought with sickness, death, and difficult journeys home. Elijah Esty, Nathaniel Clark, Thomas Billings, John Wadsworth, William Patten, James Bailey, Michael Woodcock, and James, son of Joseph Everett, were all taken sick in camp at Lake George. Some of them remained for weeks in the hospital at Albany, but for each of them a horse was purchased by their friends, and someone from Stoughton went out and brought them home.

Joseph Tucker, a minor, was brought home by his brother Uriah. John Redman took a wagon to go from Lake George to Albany, and for some reason the driver put him out of the vehicle in the wilderness, where, he affirms, he must have perished had not Sergeant Ralph Houghton of Milton happened to pass that way. Houghton took pity on him, hired another wagon to carry him to Albany, and also lent him money to buy such things as were necessary. Daniel Talbot and his 17-year-old son Amaziah both engaged in the Crown Point expedition. Amaziah was taken sick at Half Moon, and his father hired a horse to bring them home. Amaziah died en route, and Daniel returned home alone.

Yet it is the letter that we now have in our ancient Stoughton document tome that has stood the test of time. Few know of its existence, and merely a handful of historians have spent any time with this letter. It was written in that part of Stoughton that is now Canton. So strong were the words that it was published as a broadside, likely by the English colonial government as a way to build support for the campaign against the French. The letter was written by Jonathan Kiny just before the young man left for Albany for Crown Point. Historical accounts of the young ensign paint a picture of a devoted family man and member of the Church of England who grew up in the early 1700s in what is now Ponkapoag. Around 1750, Kiny (also spelled as Kenney) married Sarah Redman, the daughter of Robert Redman, one of the earliest settlers in this area.

In the dark of an early spring night, Kiny paced the floors of his small house near Potash Meadows and Aunt Katy’s Brook holding his two small children — his boy, Jonathan, just barely 2 years old, and his daughter, Cloe, age 4. Kiny’s wife had died two years earlier, perhaps after the birthing of their son. And so Kiny knew that departing for war meant that he might never look upon their sweet faces again.

The letter, written on April 16, 1756, under seal, is religious, poignant, and heart-wrenching when you consider that Kiny would die within months of writing it. “Dear children, Since God by his all-wise providence, about sixteen months ago, remove your kind and tender mother from you by death, and as I am called by Providence to go into service of my King and country, and not knowing whether ever I shall return to you again, I charge and beseech you to mind the One Thing needful, to remember your Creator in the days of your youth, to love one another, to mind religion while you are young, to be constant in secret prayer, for God loves to hear young children come to him, and though you have no father or mother he will be better to you than the most affectionate parents can possibly be … I charge you to beware of bad company … to be obedient, and often read your books … when you come to a sick bed, and a dying hour, to look back on a life well spent.”

The letter is quite long, and it ends with the premonition of Kiny’s death. “My dear children,” he writes, “I hope better things of you, and things that accompany salvation, and I charge and advise you once more to observe this council and advice; and though you may never see me again in this world, I entreat you to prepare to meet me in heaven where I hope to rest after this frail life is ended.” Kiny died in a hospital at Albany within nine months of writing the letter. Delivered to his small children, the letter contained a gold ring that he had placed on his wife’s finger six years earlier.

The children were placed in the care of their grandparents, Robert and Mary Redman, who raised them as their own. In 1757, Robert Redman executed a will in which he provided for his grandchildren, leaving six pounds, 13 shillings and four pence to Jonathan and four pounds and a good cow to Cloe when she arrived at the age of 21. The letter was published soon after his death, and one of only two known copies survive in the collection of the Canton Historical Society.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=27519