True Tales Retold

By George T. ComeauSailor, Soldier, Gentleman

This story originally appeared in the Canton Citizen on June 20, 2013.

She probably wrote dozens if not tens of dozens of letters to her husband throughout the war. Her florid handwriting curves beautifully, with an assured hand of a well educated woman. The beginning of the end was in sight, the winds of the War of the Rebellion had shifted, and as Caroline Tucker McKendry writes to her husband, her pain and suffering burns through the paper.

William McKendry Jr. was born in Canton in 1825 on the farm that had been in the family since the first settlement of Dorchester. Educated in Ponkapoag, the eldest son of Captain William McKendry and Harriet Billings, young William was set on a course of rigorous education. Attending North Yarmouth Academy in Maine, William studied the classics while his eyes were trained on the North Star, and before he turned 18 he stood “before the mast” as a sailor on East India trading voyages. After all, he was following in the footsteps of his father, who had been a master mariner in his own youth.

Within a few years William became the captain of a trading vessel and settled into a fairly well-off lifestyle of trade. Returning home to Canton in 1854 at age 29, William married Caroline Tucker, who was eight years his junior, and they lived in Ponkapoag with William returning to the sea as often as possible. William knew Caroline as simply “Caddie” and they were madly in love. The image of the brave captain and the dutiful wife is not quite the impression of this arrangement. Fiercely independent, Caddie had a career in mind for herself, not common for a woman in the mid 19th century. Becoming a writer, Caddie’s fiction was featured in the New York Ledger and Frank Leslie’s.

It is also likely that Tucker was a teacher, as she had graduated from the Bridgewater Normal School in December 1849. Within five years the family grew and William Henry McKendry was born. In 1862, William entered the service early in the Civil War. Reporting for duty at the Navy Yard in Boston, within 60 days he was headed for the West Gulf blockades aboard the USS Winona.

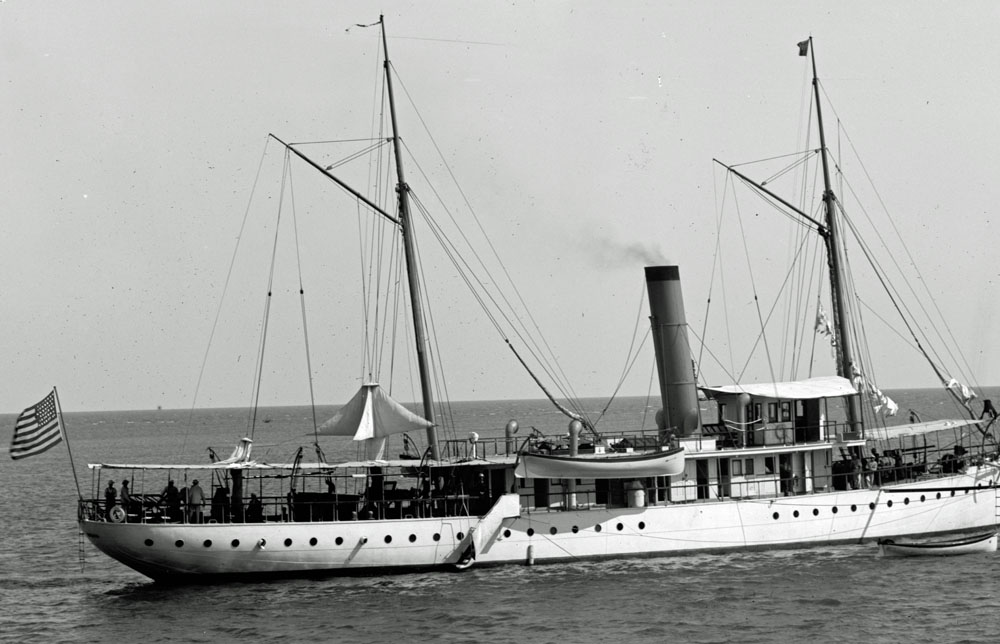

The Winona was less than a year old and a formidable part of the early war with the states. This two-masted schooner had a top speed of 10 knots and as such made an easy target. By the same measure, she was heavily armed, with large guns for duels at sea and 24-pounder howitzers for shore battles. Within days, William was in the thick of battles under the command of David G. Farragut. Achieving distinction, it is said that William was known for his “fidelity to duty and bravery and nautical skill.”

William saw plenty of action, and the tales are both heroic and horrific. Within days of his arrival on the Mississippi River, William, aboard the Winona, saw action. The logbook recounts: “Mississippi River December 14 1862, Sir, I have to report that while this vessel was at anchor near the Essex off the upper end of Profit Island just at early daylight a rebel battery of fieldpieces opened fire on her. We at once returned their fire with grape canister and shrapnel but they had taken up such a position during the night without being observed that they were enabled to rake the vessel repeatedly without our being able to return an effective fire. I attempted to heave up the anchor only having a short scope of chain out, but the enemy’s fire was so heavy and well directed that I was obliged to slip the chain. We steamed up toward the Essex and in doing so the pilots ran the vessel aground, but fortunately we backed off and made fast to the starboard side of the Essex when both vessels backed down the river. During the engagement this vessel was struck twenty seven times in the hull spars and rigging, many of the shot cutting her up badly. The enemy not noticing the Essex directed his whole fire at us. I regret to say that Acting Master’s Mate David Vincent was mortally wounded and has since died.”

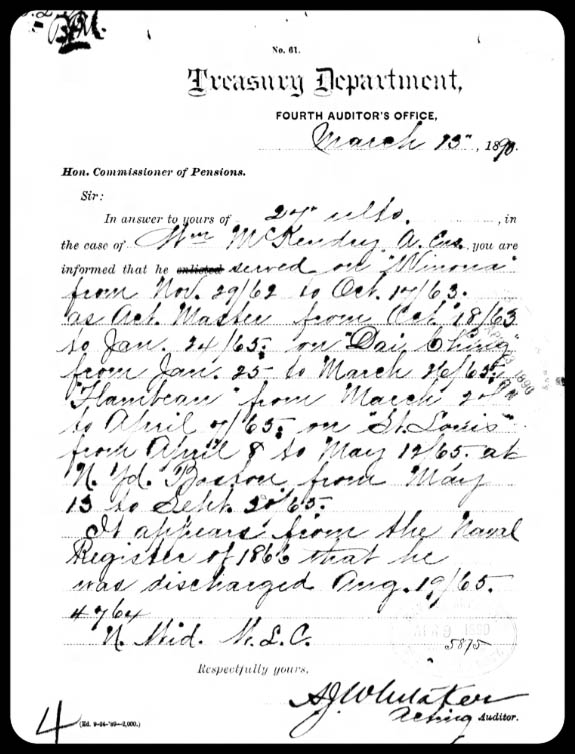

This was William’s first taste of the horrors of war, but far from his last. During the course of his service between 1862 through his honorable discharge in 1865, William served aboard four vessels. The only known surviving letter written by Caddie to William speaks of the ache of a wife and mother for her husband in the sights of a rebel bombardment.

On Saturday, March 18, 1865, the two lovers were as far away as they could possibly be. Caddie was in Ponkapoag expecting William home on furlough. She writes, “So with what zest I have rolled out pie crust. Stirred up cake and roasted beef saying jubilantly to myself — this is for Wm’s Sunday Dinner! My Darling, my precious…” William, however, was recuperating from a battle that nearly took his life and forever weakened his heart.

In January 1865, William was assigned to be on board the USS Dai-Ching, a ship originally built for the emperor of China but pressed into service as part of the war. The Dai-Ching had received orders to proceed up the Combahee River in South Carolina as far as the ferry near the Charleston and Savannah railroad. In accordance with those orders, the Dai-Ching got under way at an early hour and, after having proceeded up the river for a few miles, was fired upon by a rebel battery situated on the right river bank. The battery opened with heavy artillery pieces at short range and the ship ran aground and foundered.

William was the executive officer and second in charge of the ship. The Dai-Ching underwent the firepower of the rebel battery for seven consecutive hours. Struck more than 30 times, the 170-foot ship was a sitting duck. “Her uncomfortable position having been observed by the rebels, they re-doubled their efforts to disable her, and, in order to affect this result, several additional guns were brought into action. The officers and crew of the Dai-Ching behaved splendidly. At last, at 3 o’ clock in the afternoon, it being apparent that the vessel could not be got afloat, and that it had all hands on board would be captured unless measures were taken to prevent such an event.”

The officers decided to set fire to the ship and then abandon her. A signal of distress was hoisted from the Dai-Ching, but was ignored by the rescue ship. The men, nearly 100 of them, abandoned the ship, which quickly burst into flames as the fire spread to the ammunition supply. Reaching the marsh, the men “were compelled to wade through the weed and mud for a distance of twelve or thirteen miles before they reached a point on the bank of the river where they were rescued by the U.S. tug, Clover.” William was especially hailed for his “coolness and gallantry.”

The final resting place of Caddie and William McKendry at Canton Corner Cemetery (Photo by the author)

The effect of the battle upon William was devastating, and as he read the six-page letter aboard the USS New Hampshire, he could sense his wife’s anger and fear. “Oh my Darling! My Darling! I am cross. I am angry. I am half crying. I am almost entirely discouraged … all day long I have been whispering to myself — tonight I shall have rest and love. Wm is coming, and the night has brought the heart sickening discouraging information that you are not likely to be furloughed at all.”

The battles had been intense, and William’s heart was weakened, both figuratively and literally. Continuing his service, discharge came on August 19, 1865. But, like all soldiers who return from war, this hero was forever changed. On a warm August evening in 1876, 11 years after the battles ended, William McKendry rose from his couch in Ponkapoag to close the window. Returning to his chair, he sat down and simply died. Right there and then, his heart stopped. Caddie was a widow and knew the war had done irreparable damage to her deepest love.

William’s surgeon aboard the Dai-Ching testified on behalf of the widow’s pension request: “I remember how bravely he fought from early in the morning till we were forced to leave the vessel in the afternoon.” The surgeon attributed his death to the “great excitement and fatigue that he had been exposed to.”

At Canton Corner Cemetery is a large, splendid and impressive grave. A woman stands atop the stone, more than 15 feet tall, her left hand resting on an anchor, her right arm once held high — now lost to time. This is the McKendry grave. Caddie died in 1915 and is buried alongside her husband. And the letter, a part of Canton’s history, is on sale through a private collector on eBay. Perhaps a reader will help bring the letter home so that future generations will know the sacrifice of our sailor, soldier, and gentleman: Captain William McKendry.

Click here to read a transcript of the letter from Caddie to William McKendry.

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=21163