Outside the Whale: The Discrediting of Broad Disenchantment

By Tanya Willow

A picture’s worth a thousand words: Men in tuxedos look down from a party at the Four Seasons hotel as people in the streets protest corporate greed and economic inequality during the October 15 “Occupy Boston” event. (Tanya Willow photo)

On October 15, my family went to the Boston Book Festival to hear Pulitzer Prize winning and nominated authors speak on the dangers of a lost economic decade on scientific progress. Later that Saturday we found ourselves swept in the passions of “Occupy Boston,” which marched past the Trinity Church near the Boston Public Library where the festival was taking place — a movement which on that day had spread across the country and the world.

Before Saturday I was sure that we Americans would be immersed in our virtual worlds while our real world collapsed around us — our debt hopeless; our jobs transient; our liberties vanished. We would blame immigrants. The liberal media. Government regulations. With new laws that allowed corporations to blatantly buy elections, the American experiment of the self-governed seemed all but over.

After Saturday I wonder if perhaps there is hope for this republic.

In 1978, 30 years before the start of the great economic cataclysm we are now struggling with, I graduated from high school. By the time I graduated from Curry College in Milton in the early 1980s, like now, around 10 percent were unemployed. My tuition was subsidized by Social Security (a young widow/student benefit Reagan eliminated in 1981) and was relatively low so, unlike today, most of us started life with little debt.

I came out of college and worked part-time jobs with no benefits for several years. Even today, few in my circle have jobs with pensions, just worthless mutual funds stripped bare by invisible managing fees. I recently read an article that mine is a severely underpaid graduating class. We have an aversion to risk-taking. We do not aggressively seek raises. We don’t hop from employer to employer for opportunity. We hang on to what we have and feel lucky to have it. We started our careers with lower wages, and statistics show time has not helped us to catch up.

I fear that these terrible times will produce a graduating class similar to my own — a group that lives at home too long in a kind of indefinite adolescence. A group that has no confidence in its ability to earn money, lacks financial self-worth, and slumbers into the responsibilities of adulthood in the mid-afternoon of life.

Hard economic times create hard political views. My contemporaries are right wing. We loved Reagan, who shed us of our Vietnam shame and made war popular again. We chanted for the nuking of Iran and blamed welfare mothers for our economic troubles. (Immigrants weren’t given a thought.) If the mentally ill, who were de-institutionalized, ended up freezing in the streets, it was because they wanted to be homeless. If you failed in early 1980s America it was because you weren’t trying hard enough.

Hard economic times create hard political views. My contemporaries are right wing. We loved Reagan, who shed us of our Vietnam shame and made war popular again. We chanted for the nuking of Iran and blamed welfare mothers for our economic troubles. (Immigrants weren’t given a thought.) If the mentally ill, who were de-institutionalized, ended up freezing in the streets, it was because they wanted to be homeless. If you failed in early 1980s America it was because you weren’t trying hard enough.

The difference between this generation and mine is that rather than blaming the least powerful for their problems, they are accusing the puppet masters — the infamous 1 percent — and voicing their accusations on the streets, which at least seems more self-determining than how my age group coped with joblessness, with inner shame and outward cruelty.

Within 24 hours, former Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney, who has been groomed for years to be the nation’s next corporate president, went from calling the Occupiers “dangerous” to saying he “worries about the 99 percent.” And Governor Patrick — who has an attraction to opulence (curtains and Cadillacs) and who has snuggled his nose against the necks of the most powered corporations — came striding down to speak with the protesters without his entourage, stage flats and television lights.

Congressmen Barney Frank was at Wheaton College recently and was asked by my husband if the Occupy movement was putting pressure on Congress. He said they were putting more pressure on the grass under their feet. The following day, at Canton’s Town Hall, Congressman Stephen Lynch was asked the same question. He said in essence that the Occupiers’ message is too broad to be effective.

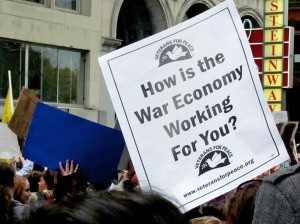

Perhaps Congress today is so accustomed to having specific legislation written for them by lobbyists that they no longer can comprehend “broad” public needs. “End the War. Tax the Rich.” “How’s the war economy working out for you?” or “I’ll believe corporations are people when Texas executes one” can only be fixed through laws Congress itself would have to write. But that legislation would run contrary to the 1 percent’s agenda, and so our representatives shrug their shoulders and act as if they have no idea what the Occupiers are talking about.

But “We the People” can still vote, and so the always gutless Democrats aren’t sure if they should hook their wagon on this train. Great numbers of people protesting instinctively against forces over which they have no control is by its nature unpredictable and easily infiltrated. Nixon had the Teamsters smash heads to horrify the public during anti-war protests. It would not take much to discredit the Occupiers, and no politician wants to be affiliated with something that could go so easily and terrifyingly awry.

Yet the sheer organization of the Occupy movement is formidable, smartly using social networks to gain the public’s attention while the media ignored or berated them. And they are not all young. I was struck by the number of baby carriages in the street Saturday. As the marchers look more and more like voters, Congress may have to get up from their breakfast tables with lobbyists and look out the window and down at the street to those they are supposed to be representing.

Yet the sheer organization of the Occupy movement is formidable, smartly using social networks to gain the public’s attention while the media ignored or berated them. And they are not all young. I was struck by the number of baby carriages in the street Saturday. As the marchers look more and more like voters, Congress may have to get up from their breakfast tables with lobbyists and look out the window and down at the street to those they are supposed to be representing.

While the protesters headed toward Boylston Street, the three authors speaking in the Trinity Church talked of an approach to life that lies in the rational. Despite the church setting, the promise that the meek shall inherit the earth and that the rewards for those born to be ruled comes after death was remote. Here the approach of the ancient Greeks was evoked — the idea that Being is transitory, yet all the universe, the inhabiters of this earth included, is made up of the same eternal material. That for us, meaning to our lives is found when we realize this brief incarnation in the mortal world is enough. That in politics and life, there are no saviors.

As a marcher’s sign so succinctly expressed, “We are the ones we’ve been waiting for.”

Short URL: https://www.thecantoncitizen.com/?p=9049